"Yellow Vest" ? The Majority of French People Are Among the Richest 10% in the World

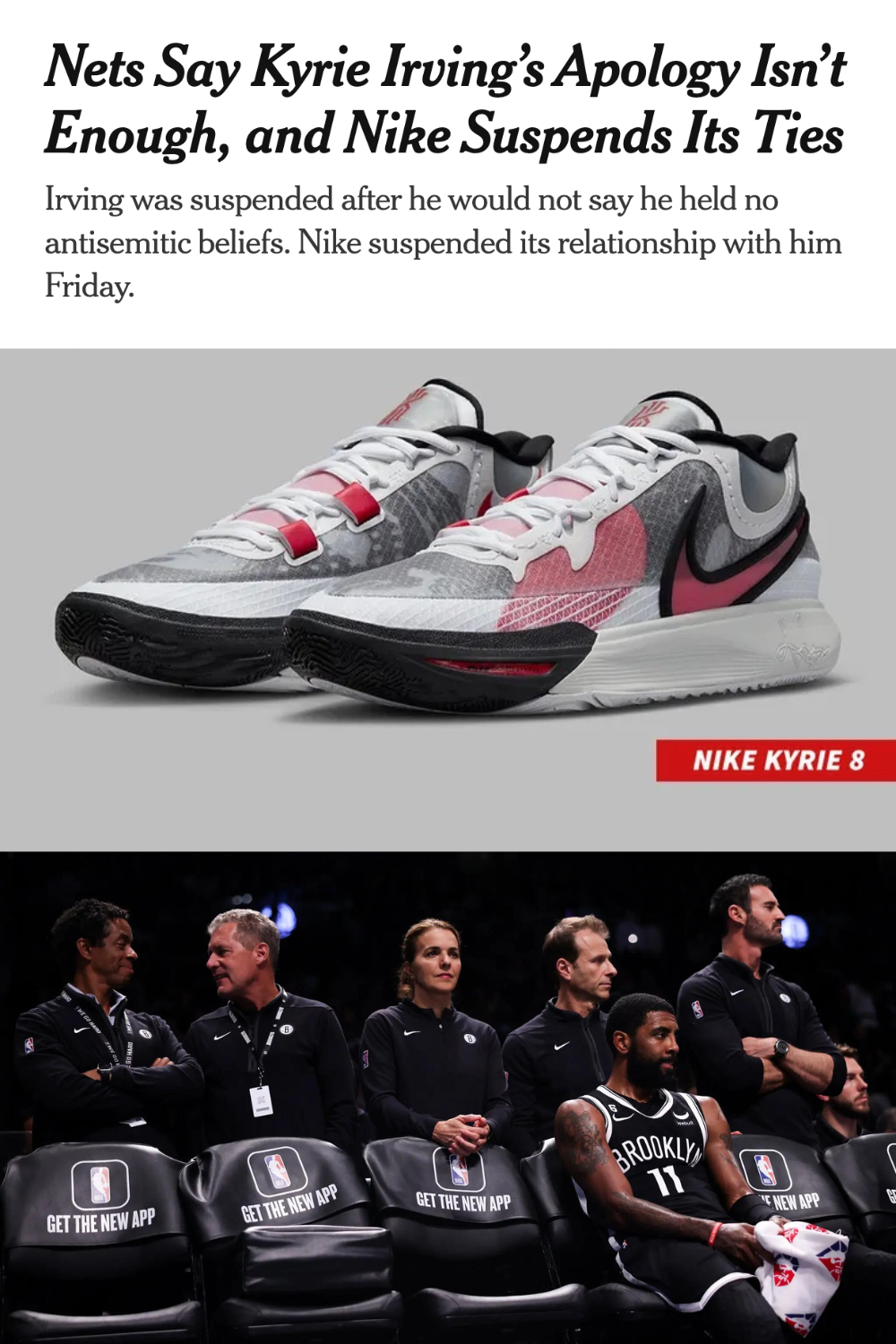

/Gilets jaunes empêchés de rejoindre la place de la République et attendant d'être débloqués de la place de la Bastille par les forces de l'ordre. 26 janvier 2019.. By Thomon - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0. via Wiki Commons.

By Speranta Dumitru, Associate Professor, Paris Descartes University. First published on The Conversation

In France, the concern for inequality makes poverty invisible. For example, the organization Oxfam, whose name is related to the famine ( Ox ford Committee for Fam ine Relief), focused his campaign on the rich. The media gave the names of billionaires who would own as much as half of humanity but did not say a word about the poor. Yet, naming poor people increases their sympathy for them and promotes altruistic decision, as many studiesshow.

The invisibility of the poor could be explained by the current context. After long months of saying that yellow jackets "suffer", that they are "in distress" and can not "make ends meet" or "fill their fridge", can we still talk about those who live on $ 1.90 a day?

There is certainly good news: the proportion of the world's poor has fallen drastically. Forty years ago, it was over 40%. Today, only 10% of the world's population lives on $ 1.90 a day. Half of these people live in Africa.

So, imagine that you have 100 euros to give. You can give them to Christian, one of my students, born in Burkina Faso: he will send them to his family who live with $ 1.90 a day, as nearly half of Burkinabe. But you can also give them to Eric, father and driver, who earns a little more than 54 euros per day, the value of the daily smic.

How are you going to spend those 100 euros?

The national preference

Like most French people, you are tempted to give Eric the money. Admittedly, you know that 100 euros are worth a lot more for Christian. And you know that with the same money, you would help more people because family solidarity is more widespread in Africa. But something bristles you in this reasoning.

The temptation to favor his relatives and, by extension, his compatriots, is quite natural. In his Theory of Moral Sentiments , Adam Smith noted that any European of humanity would deplore an earthquake that touches a distant country. But despite the intensity of the disaster and the millions of inhabitants concerned, his personal belongings seem to him more important.

Now this attention to ourselves and to our surroundings perverts our moral sense. With the emotions that play tricks on us, we lose, as this European of whom Adam Smith speaks, any sense of the measure:

"If he were to lose his little finger, he would not sleep at night; but he would snore with the deepest sense of security in spite of the ruin of a hundred million of his brothers, provided he had never seen them. "

To avoid being trapped by our inclinations, John Rawls has found a solution. He called it "veil of ignorance". His idea is that it is not enough to want to be impartial (because our inclinations can take over). In terms of social justice, we must rather reason as if we did not know what social position would be ours. Basically, we could have been born in a rich or poor family. Our birth is more a matter of luck than merit.

This changes the problem a bit: imagine that you no longer have to give 100 euros but to receive them. But tomorrow morning, the birth lottery will be played again and you will wake up either in Christian's life or in Eric's life. You do not know how luck will turn, but you will have to live this life, drawn by lot, to the end - whether in France or Burkina Faso. In the meantime, tonight, we ask you where to send the 100 euros, in France or Burkina Faso?

Thousands of yellow vests (Gilets Jaunes) protests in Paris calling for lower fuel taxes, reintroduction of the solidarity tax on wealth, a minimum wage increase, and Emmanuel Macron's resignation as President of France, 09 February 2019. By Norbu Gyachung, CC BY-SA 4.0. via Wiki Commons.

Is living in France a chance?

Many people think that living in France is not really a chance when you are part of the working class.

The economist Branko Milanovic is the first to have estimated the extent of inequality of opportunity globally. He analyzed household disposable income in 118 countries. For each country, it divided the population into 100 shares and recorded the income of each 1%, or percentile. In total, he had 11800 centiles. But he wanted to know if the poorest 1% in Brazil, for example, are richer than the poorest 1% in India. To be able to compare these incomes, he converted them using purchasing power parity (PPP). Then, he reordered them by percentiles around the world.

For France, data from the World Bank show that 62% of French people belong to the richest 10% of the world.

But public opinion is interested in the very rich. In the graph below, each point represents 1% of the French with its rank in the national (on the horizontal axis) and the global (on the vertical axis) income distribution. On the right of the graph, we see that the richest 3% of the French are among the richest 1% in the world. In the United States, 12% belong to this category.

If public opinion is more interested in the poor French, it would look, for example, the first point on the left: it is the poorest 1%. She would be surprised then that despite their position, rather away from the rest of the national distribution, nobody cares. With their close proximity to the global distribution community, their buying power resembles that of the world's middle class , most of whom live in China.

Above the 3% poorest in France, the situation is improving rapidly, so that 97% of the French belong to the 30% richest in the world. Then, 90% of the French are among the richest 20% in the world.

Therefore, if the lottery has awarded you the life of Eric in France, you are literally lucky. Because, whatever your personal efforts, the country where you are born determines your income prospects. Branko Milanovic estimated that place of birth accounts for 80% of global inequalities . His book, Global Inequalities , has just been translated into French.

At such a level of inequality of opportunity, one can not hesitate between Eric and Christian. Christian's family will almost certainly live on less than $ 5.50 a day, like 92% of Burkinabes . For Eric's child, the probability of having such income is 0.2% in France.

These comparisons take into account prices in each country, as indicated by the term "purchasing power parity". If the purchasing power of yellow vests justifies anger, how to call the feeling that the Burkinabés smother?

How to reduce inequality of opportunity?

Two solutions are often discussed in the public debate: the opening of the labor market to foreigners and redistribution.

Milanovic defends the first solution: to increase labor migration. This is the classic solution in development economics. Lant Pritchett , Harvard professor, has dedicated a book to him, Let Their People Come , which he left in free access. My study, "Visas, not help! " , Provides an overview of these issues.

Milanovic is aware of the rise of the extreme right and proposes a compromise: increase the number of economic migrants in exchange for the reduction of their rights. For example, they could pay more taxes. But my students who read his book and are not migrants have deemed this proposal of discrimination repugnant. Their reaction suggests that a compromise between the extreme right that no longer wants migrants and young French, committed to equal treatment on the territory, is not easy to find.

Another solution: the massive redistribution of income. Oxfam, like many others on the left, consider that the rich should be taxed more. But now the tax is collected nationwide and most billionaires live in rich countries. Taxing the rich more in rich countries is obviously not a solution for Africa.

Moreover, public opinion considers any tax exile as illegitimate, as if only their compatriots were entitled to benefit from the tax collected on these billionaires. At no time does one wonder whether the exile of the rich benefits the poor.

For the moment, the two solutions envisaged to reduce the inequality of chances lead to dead ends. On the one hand, the Milanovic compromise is difficult to obtain in a context of strong polarization of opinion. On the other hand, public opinion cares more about taking to the rich than improving the lives of the poor.

As for Emmanuel Macron, his solution is to promote access to the French labor market. Thus, the measures proposed in the crisis of yellow vests encourage work: increase of 100 euros for those who work for 0.5-1.5 of the smic and tax exemption of extra hours of work. It is clear that these measures will increase the inequality of opportunity at the global level.

While waiting for better times, we will have to redouble our efforts. We are more than half of the French to be part of the 10% richest in the world. Our efforts should be aimed at helping the poorest and the associations that fight poverty effectively.

![Kanye West's [aka Ye] Refusal to Treat His Mental Illness Is No Excuse For His Anti-Semitism](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1666238183530-4WVG9SNG88HTSKQ0WWDV/Is+Kanye-West-Running-Out-of-Platforms.png)