There Is More Than One Religious View On Abortion -- Here's What Jewish Texts Say

/By Rachel Mikva, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies, Chicago Theological Seminary. First published on The Conversation.

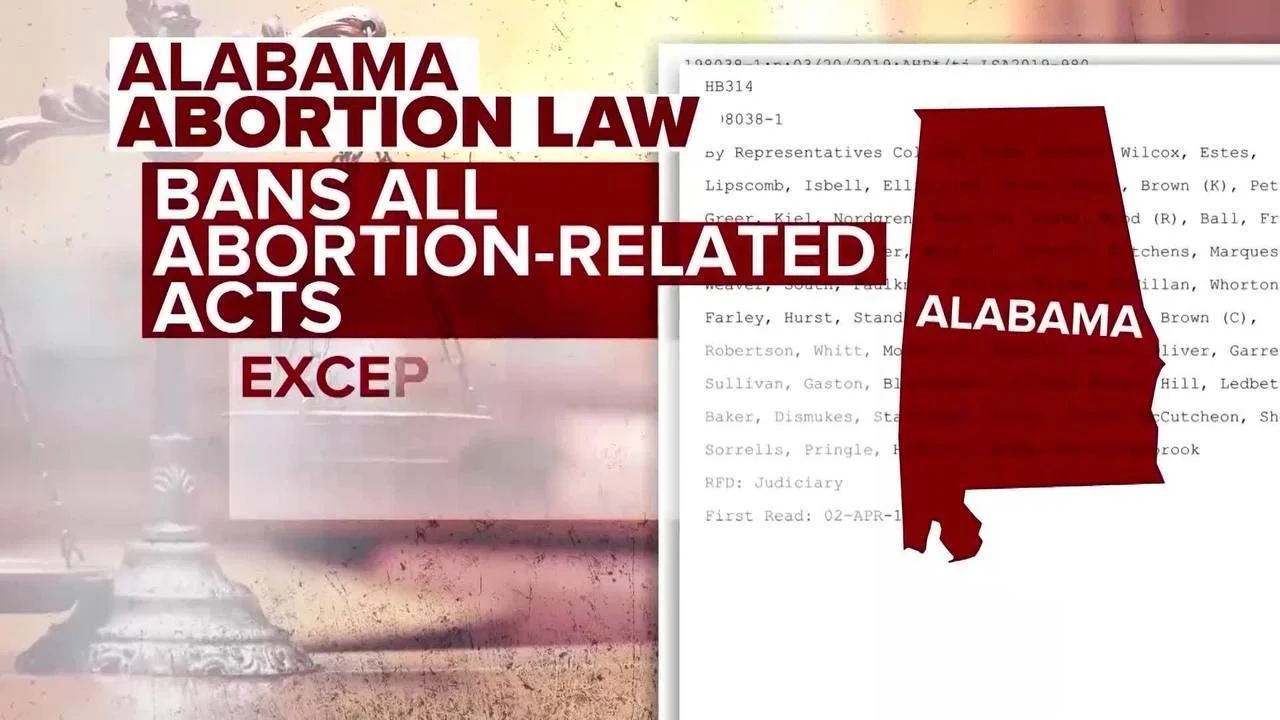

Alabama’s governor signed a bill this week that criminalizes nearly all abortions, threatening providers with a felony conviction and up to 99 years in prison.

It is one of numerous efforts across the United States to restrict access to abortion and challenge the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade that legalized abortion nationwide.

Six states have recently passed legislation that limit abortions to approximately six weeks after the end of a woman’s last period, before many know they are pregnant. Although the laws have not yet taken effect and several have been blocked on constitutional grounds, if enacted they would prohibit most abortions once a doctor can hear rhythmic electrical impulses in the developing fetus.

Called “fetal heartbeat” bills, they generally refer to the fetus as an “unborn human individual.” It is a strategic choice, trying to establish fetal personhood, but it also reveals assumptions about human life beginning at conception that are based on particular Christian teachings.

Not all Christians agree, and diverse religious traditions have a great deal to say about this question that gets lost in the polarized “pro-life” or “pro-choice” debate. As an advocate of reproductive rights, I have taken a side. Yet as a scholar of Jewish Studies, I appreciate how rabbinic sources grapple with the complexity of the issue and offer multiple perspectives.

What Jewish texts say

Traditional Jewish practice is based on careful reading of biblical and rabbinic teachings. The process yields “halakha,” generally translated as “Jewish law” but deriving from the Hebrew root for walking a path.

Even though many Jews do not feel bound by “halakha,” the value it attaches to ongoing study and reasoned argument fundamentally shapes Jewish thought.

The majority of foundational Jewish texts assert that a fetus does not attain the status of personhood until birth.

Although the Hebrew Bible does not mention abortion, it does talk about miscarriage in Exodus 21:22-25. It imagines the case of men fighting, injuring a pregnant woman in the process. If she miscarries but suffers no additional injury, the penalty is a fine.

Since the death of a person would be murder or manslaughter, and carry a different penalty, most rabbinic sources deduce from these verses that a fetus has a different status.

An early, authoritative rabbinic work, the Mishnah, discusses the question of a woman in distress during labor. If her life is at risk, the fetus must be destroyed to save her. Once its head starts to emerge from the birth canal, however, it becomes a human life, or “nefesh.” At that point, according to Jewish law, one must try to save both mother and child. It prohibits setting aside one life for the sake of another.

Although this passage reinforces the idea that a fetus is not yet a human life, some orthodox authorities allow abortion only when the mother’s life is at risk.

Other Jewish scholars point to a different Mishnah passage that envisions the case of a pregnant woman sentenced to death. The execution would not be delayed unless she has already gone into labor.

In the Talmud, an extensive collection of teachings building on the Mishnah, the rabbis suggest that the ruling is obvious: the fetus is part of her body. It also records an opinion that the fetus should be aborted before the sentence is carried out, so that the woman does not suffer further shame.

Later commentators mention partial discharge of the fetus brought on by the execution as an example – but the passage’s focus on the needs of the mother can also broaden the circumstances for allowing abortion.

Making space for divergent opinions

These teachings represent only a small fraction of Jewish interpretations. To discover “what Judaism says” about abortion, the standard approach is to study a variety of contrasting texts that explore diverse perspectives.

Over the centuries, rabbis have addressed cases related to potentially deformed fetuses, pregnancy as the result of rape or adultery, and other heart-wrenching decisions that women and families have faced.

In contemporary Jewish debate there are stringent opinions adopting the attitude that abortion is homicide – thus permissible only to save the mother’s life. And there are other lenient interpretations broadly expanding justifications based on women’s well-being.

Yet the former usually cite contrary opinions, or even refer a questioner to inquire elsewhere. The latter still emphasize Judaism’s profound reverence for life.

According to the 2017 Pew survey, 83% of American Jews believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. All the non-orthodox movements have statements supporting reproductive rights, and even ultra-orthodox leaders have resisted anti-abortion measures that do not allow religious exceptions.

This broad support, I argue, reveals the Jewish commitment to the separation of religion and state in the U.S., and a reluctance to legislatemoral questions for everyone when there is much room for debate.

There is more than one religious view on abortion.

Wilshire Boulevard Temple Torah Study

![Kanye West's [aka Ye] Refusal to Treat His Mental Illness Is No Excuse For His Anti-Semitism](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1666238183530-4WVG9SNG88HTSKQ0WWDV/Is+Kanye-West-Running-Out-of-Platforms.png)