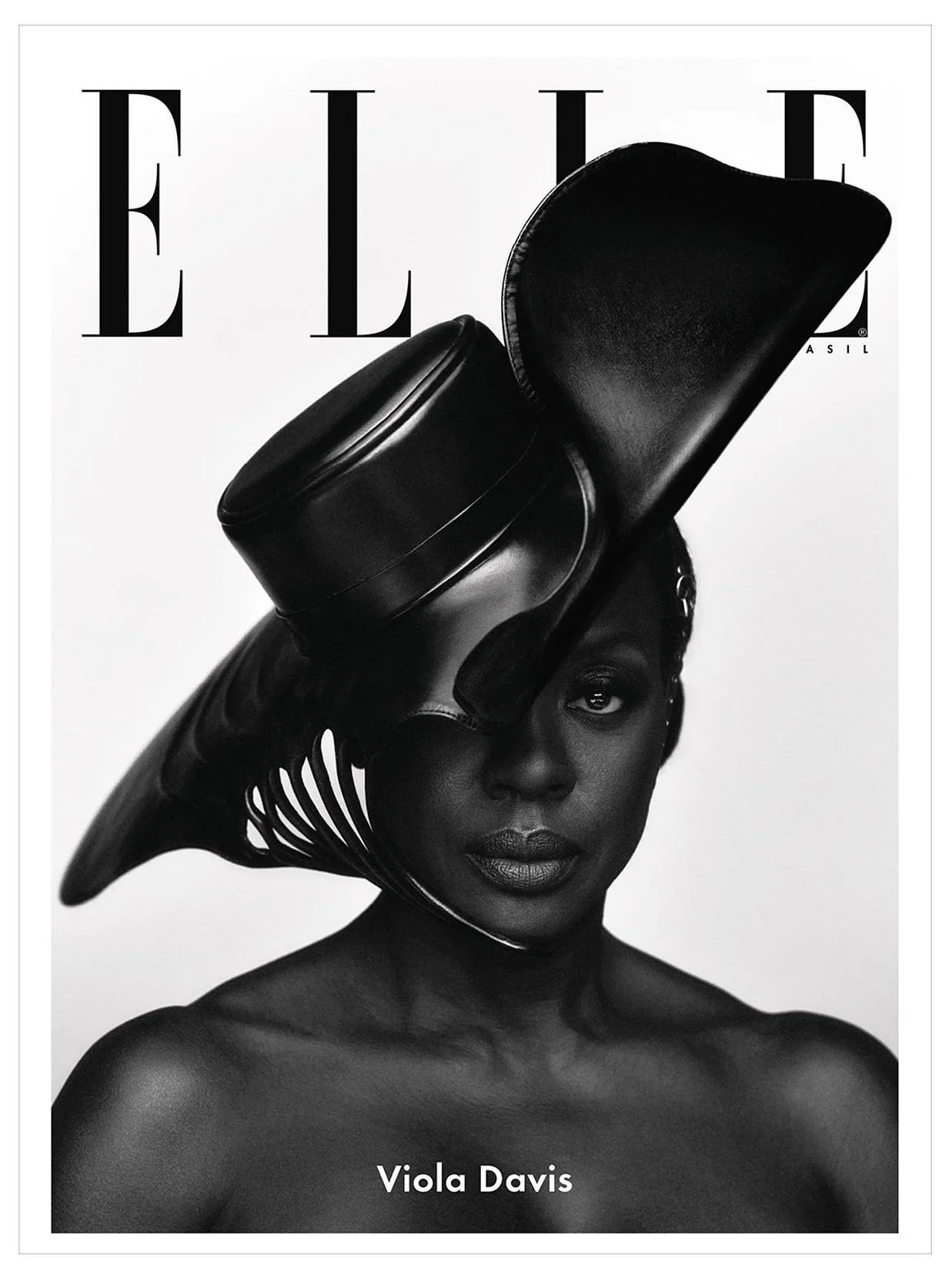

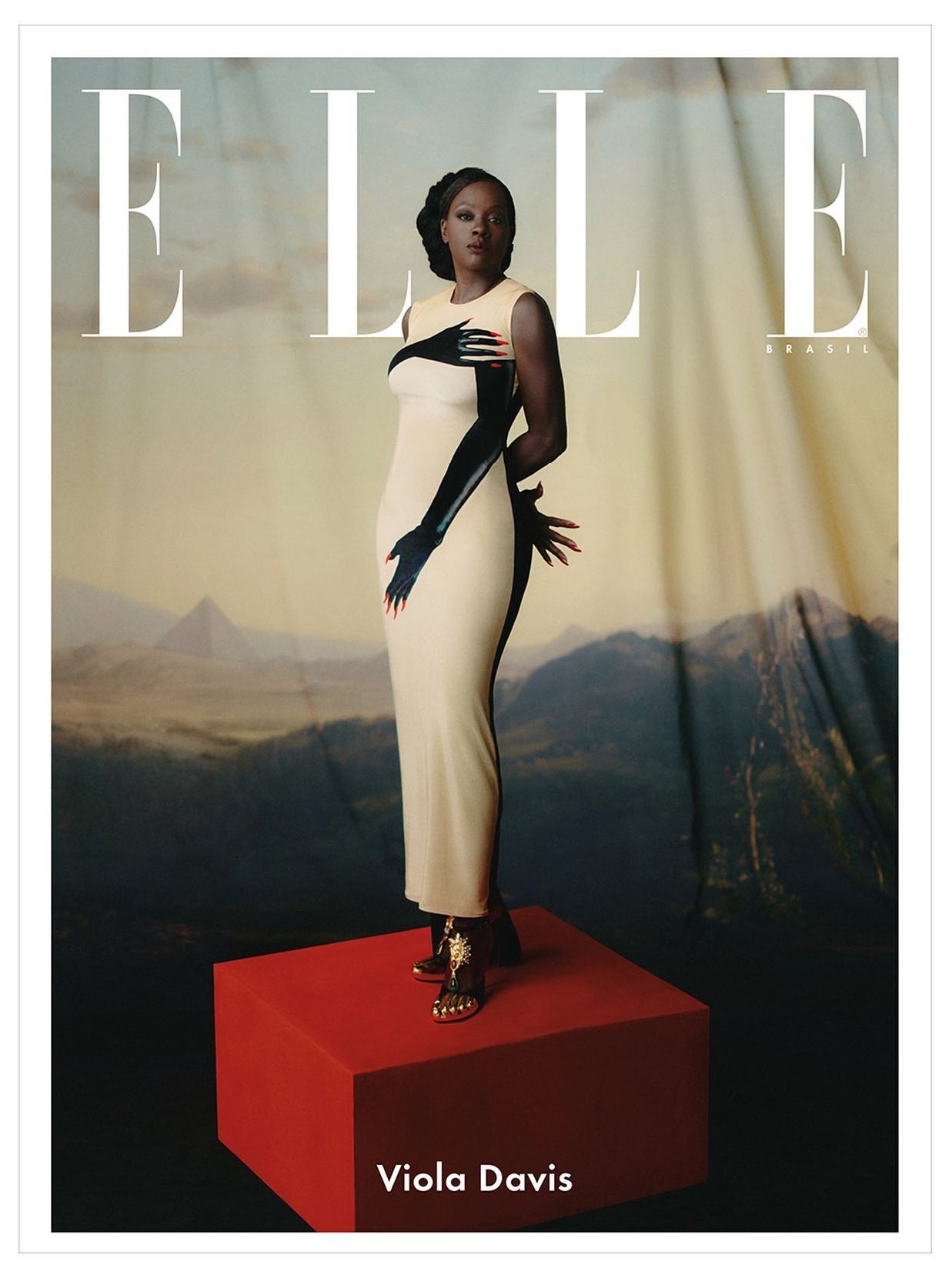

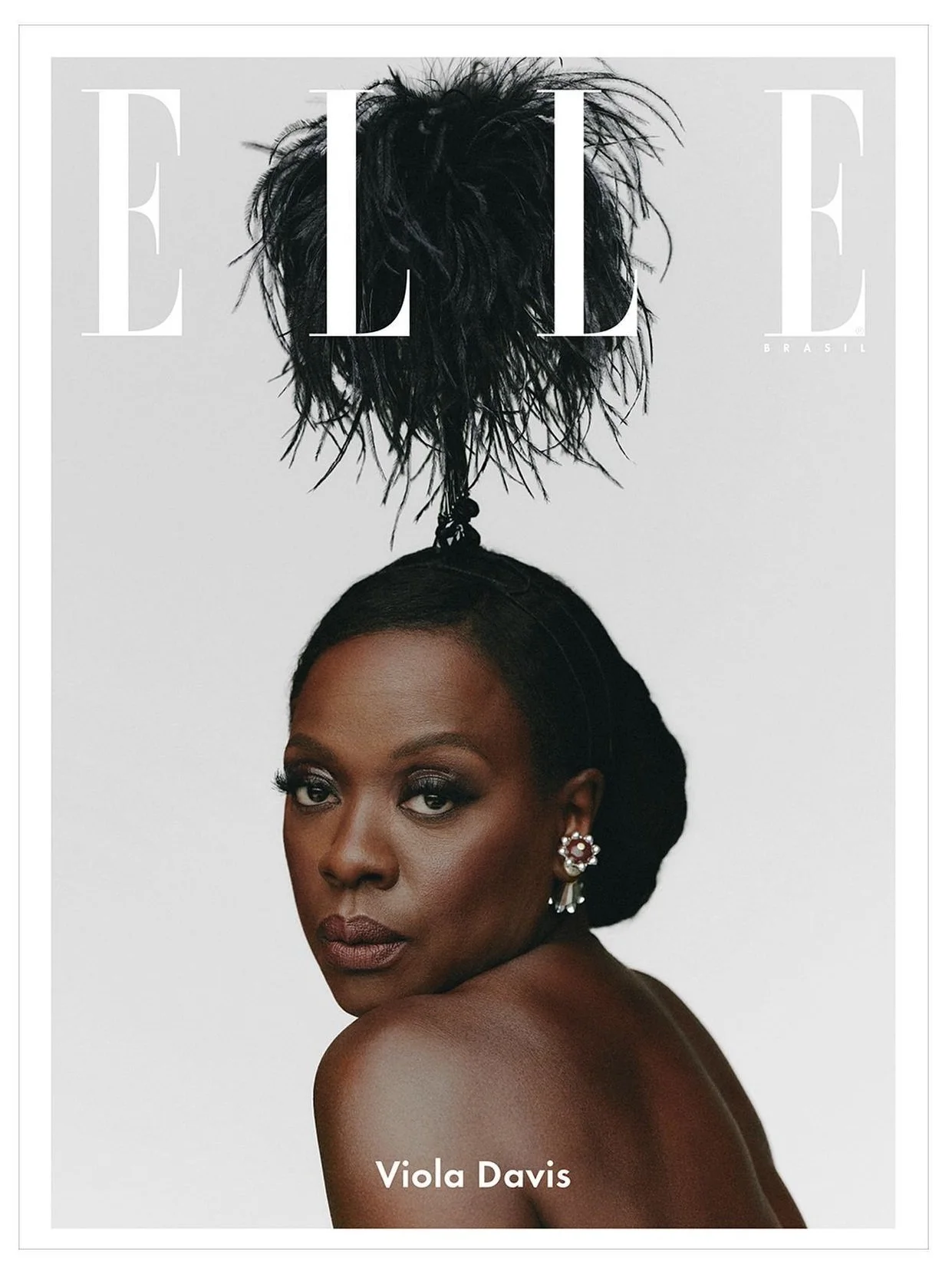

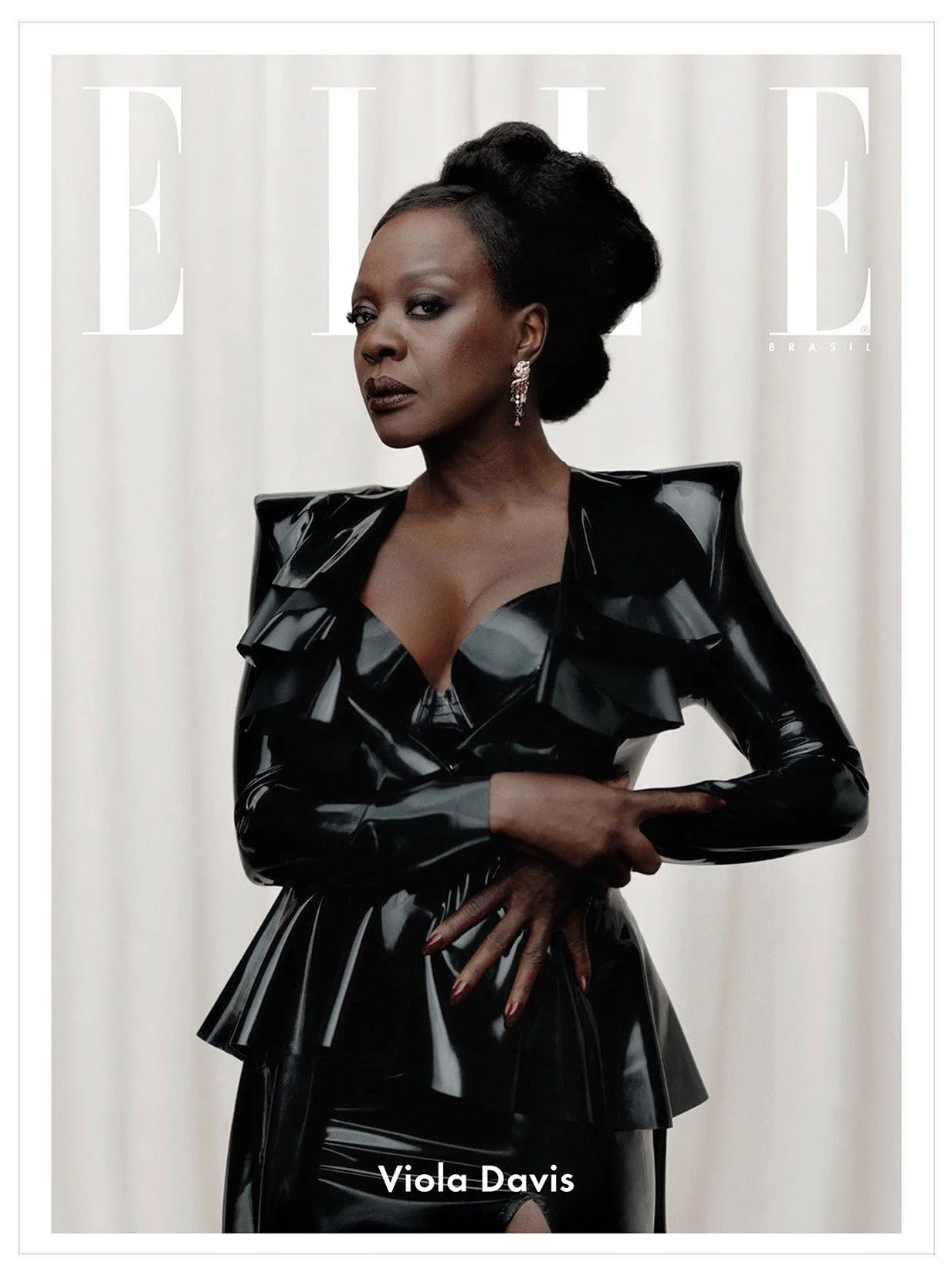

Viola Davis Comes to Life As 'The Woman King' in ELLE Brazil October by Mar + Vin

/All reports are that ‘The Woman King’ reigns supreme at the Toronto International Film Festival, which opened on September 8 and closes on Sunday, September 18.

Gina Prince-Bythewood directed the historical epic set in West Africa in 1823. Tony and Oscar award winner Viola Davis, featured here in four covers of the October 2022 issue of ELLE Brazil, stars as Nanisca, a force of nature in Dahomey, West Africa. Today Dahomey is located in what we know as southern Benin.

Brazil’s photographers Mar + Vin [Marcos Florentino + Kelvin Yule] [IG] photograph Davis, styled by Juliana Jimenez for editorial director Susan Barbosa [IG].

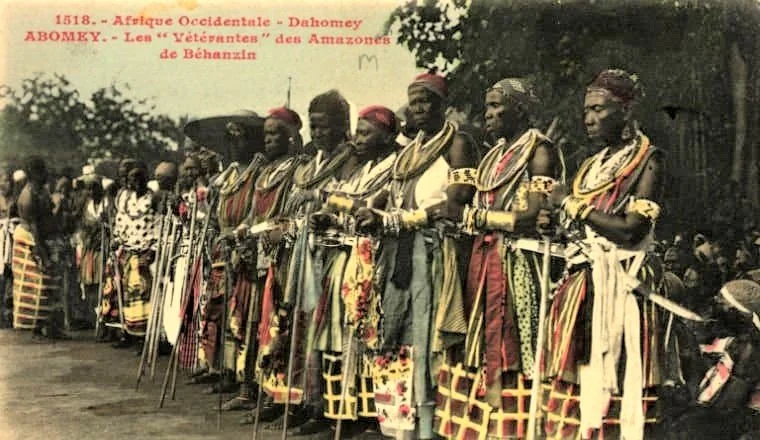

As the leader of the Agojie, the all-woman army of the African kingdom, Davis’s character led a fighting force so fierce that even enemies spoke of its “prodigious bravery”.

Damoney’s 6.000 warrior women raided villages under darkness, taking captives while beheading resisters, as trophies of war. The Agojie commanded the respect of European visitors, who often compared them to the ‘Amazons’, the legendary warrior women — now confirmed as real by researchers — of Greek mythology.

The film opens in America Friday, September 16, and the formidable presence of Viola Davis will touchdown in Brazil, to promote the release of ‘The Woman King’ on September 22.

‘The Woman King’ is the first time that the American film industry has dramatized the ferociously compelling, and disruptive-to-all-psyches story of these legendary warrior women. The film takes place against the backdrop of regional conflicts engulfing the region and the looming probability of European colonization.

The film comes at an important time in America as MAGA-Republicans seek to shut down the stories of slavery and colonialism, for fear of the truths of history becoming better known to America’s kids and old people, both.

This recent Smithsonian article reminds us that dramatic liberties have been taken with the film. As we work hard to speak to the truth of the slave trade, historians agree that the film is not telling a factual story in many areas.

I can’t believe that Viola Davis won’t work to discuss these realities — or post a well-researched counter narrative.

In our already-fraught state of race relations in America, the Smithsonian argues that:

“ . . . the kingdom’s involvement in the slave trade doesn’t align as neatly with the historical record. As historian Robin Law notes, Dahomey emerged as a key player in the trafficking of West Africans between the 1680s and early 1700s, selling its captives to European traders whose presence and demand fueled the industry—and, in turn, the monumental scale of Dahomey’s warfare.”

Make no mistake that the right-wing will seize upon these alleged discrepancies, which is why AOC will explore them in-depth out of the gate.

Just as Southenerns have rewritten the alleged glory of the Confederacy to be factually incorrect, they should understand — and have no issue with — factual changes in the history of Dahomey for the purposes of a dramatization of this African nation’s powerful women warriors.

As we really rev up this The Wokes channel, I am consolidating content from all over the website. Much of it is a decade old or even older.

Ever since Charlottesville and then the murder of George Floyd in 2020, followed by my then move to Virginia in an effort to better understand the American story, I’ve read stories about lynching and burning people in alive in America that sent me into a deep depression.

I’ve wept so many tears post-George Floyd that I contracted an eye infection and the Black doctor who treated me said “Miss Anne, you have to stop weeping. No matter what I give you to stop the infection, it won’t work if you keep crying.”

I saw a broadcast today of a youngish man speaking from Texas, and he said something that rang very true to me. His argument is that when the newspaper images from lynchings — often a form of entertainment in America memorialized on postcards — or images in the Smithsonian collections are shown online by websites like Anne of Carversville, people are going to recognize faces that are in family albums all over America.

So I understand that if AOC writes about real history vs the storyline in ‘The Woman King’, that I have a one-to-one obligation to share the American horror stories that have upset me so deeply and should not be buried from the facts of racial history in this country. This is the promise I make for Anne of Carversville.

It’s a fact that I won’t win any popularity contests — as truth-tellers always upset people on all sides — but this is the best way forward for me and the readers who trust me. Just know that the land below me was a Confederate rest station/hospital during the Civil War.

Now that is a trip for a Yankee like me!

I knew about the Dahomey Amazons, after posting this article about powerful West African women several years ago. Let me be clear that no one challenges the history of these ferocious women. The challenges come around the avoidance of confronting African participation in the slave trade. This is NOT a new topic in America’s race war of facts.

In the film Nanisca disapproves of the slave trade after experiencing its horrors personally. She urges Ghezo to end Dahomey’s close relationship with Portuguese slave traders and shift to production of palm oil as the kingdom's main export.

The Smithsonian says history is well documented that in real life:

In truth, Ghezo only agreed to end Dahomey’s participation in the slave trade in 1852, after years of pressure by the British government, which had abolished slavery (for not wholly altruistic reasons) in its own colonies in 1833. Though Ghezo did at one point explore palm oil production as an alternative source of revenue, it proved far less lucrative, and the king soon resumed Dahomey’s participation in the slave trade.

What we know for sure is that Viola Davis — and all that she stands for — reigns supreme. Davis is always at the center of swirling cultural vibrations and all women — not only women of color — should be thrilled with this historical, cinematic narrative.

Those of us who are deep researchers into the facts of history know that the patriarchy is real and has had dramatic impact on the lives of all women. We also know that there is strong evidence of African cultures where women had much more power and influence than those women who landed on American shores on the Mayflower. Their societies were often notably more egalitarian, until slave traders, colonizers and Christianity got involved in their affairs.

To be continued . . . Anne