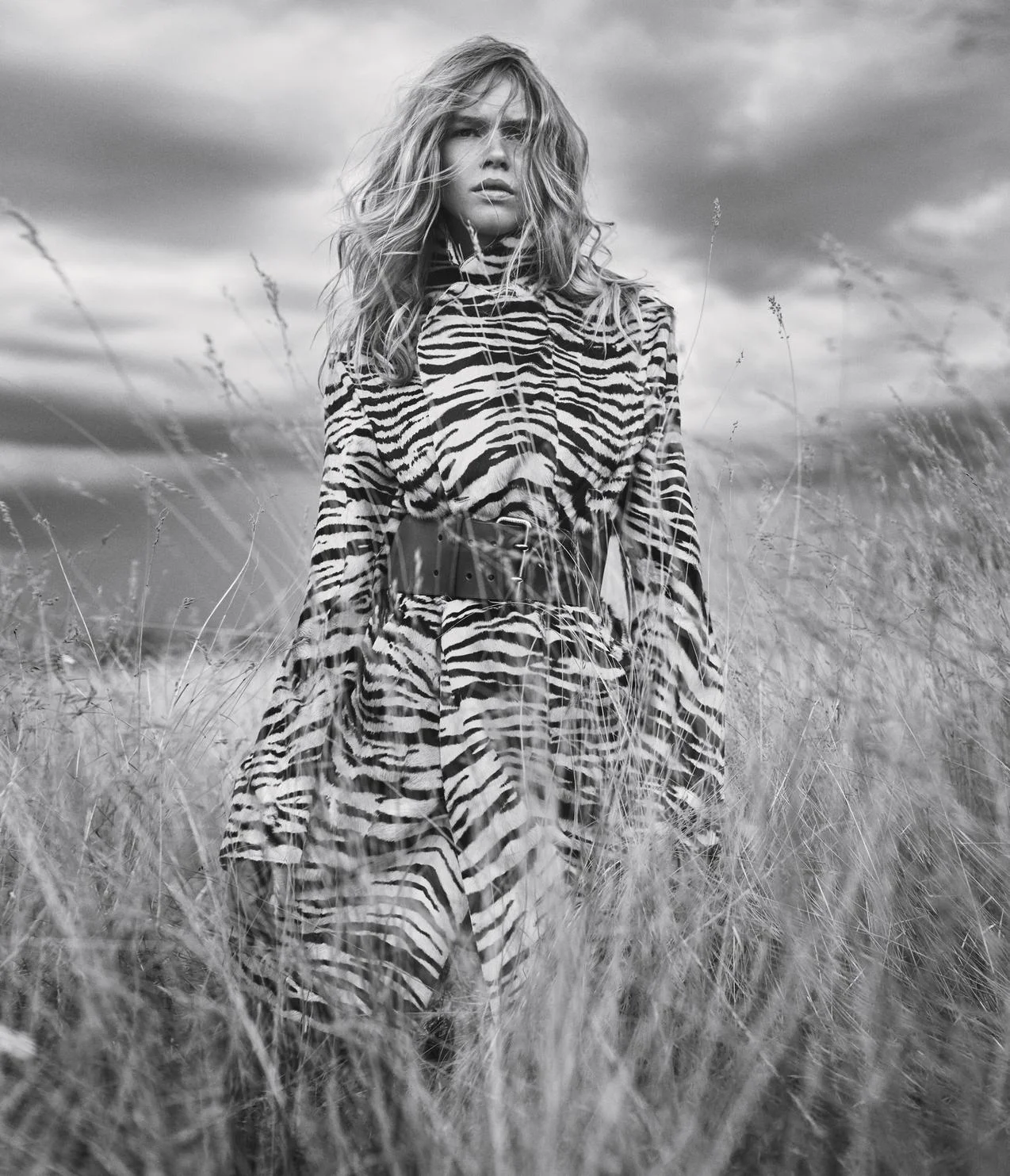

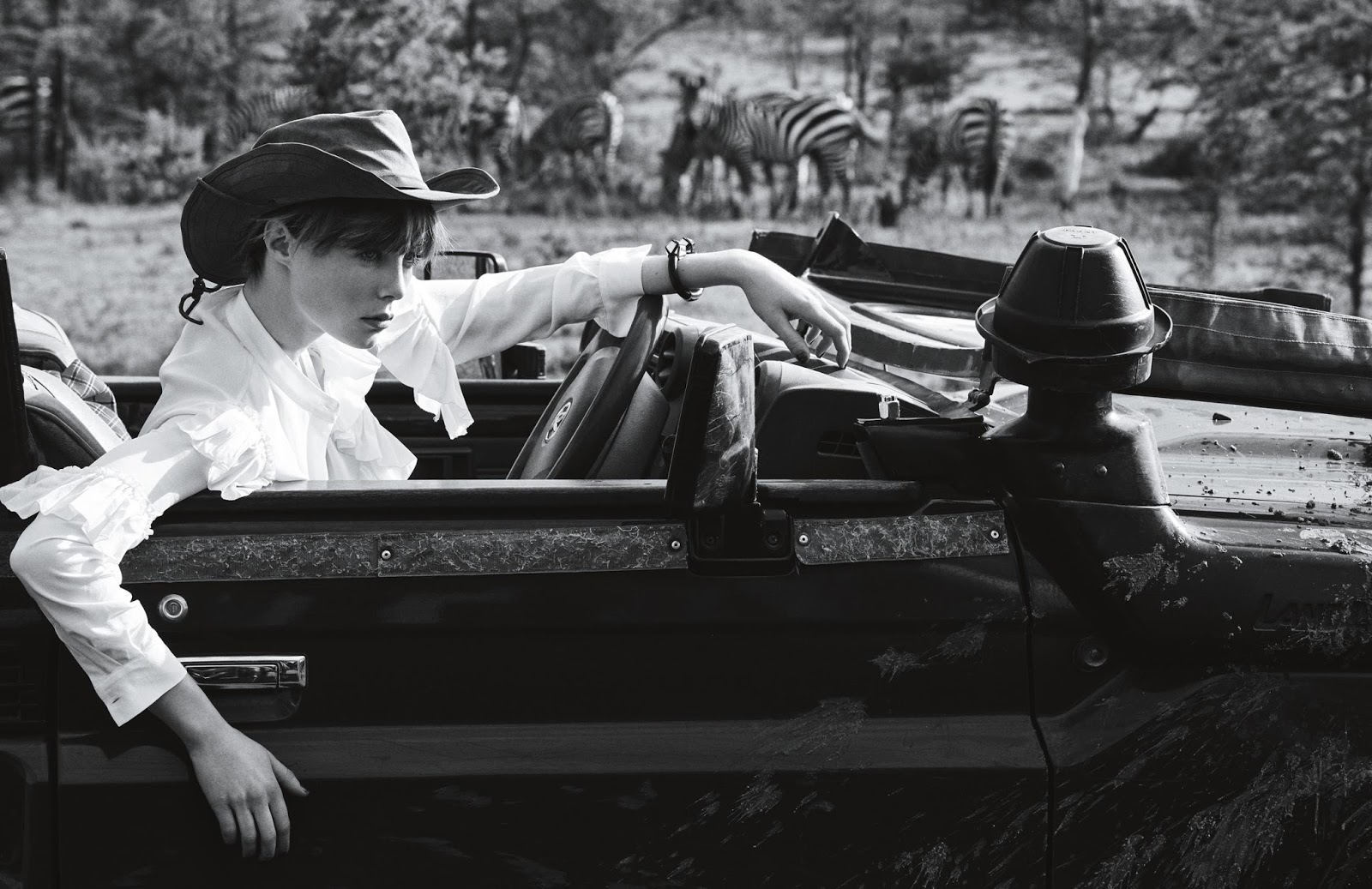

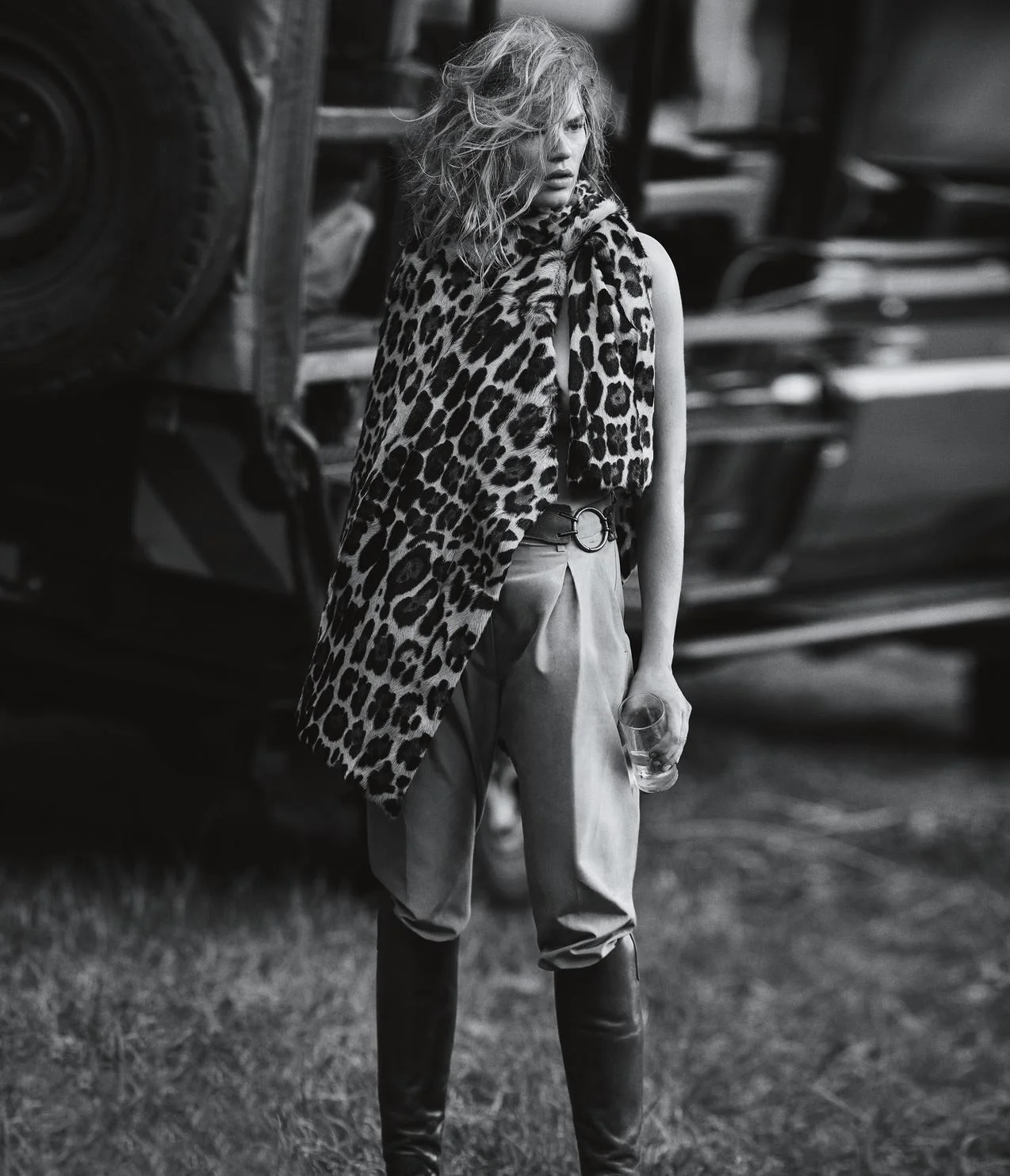

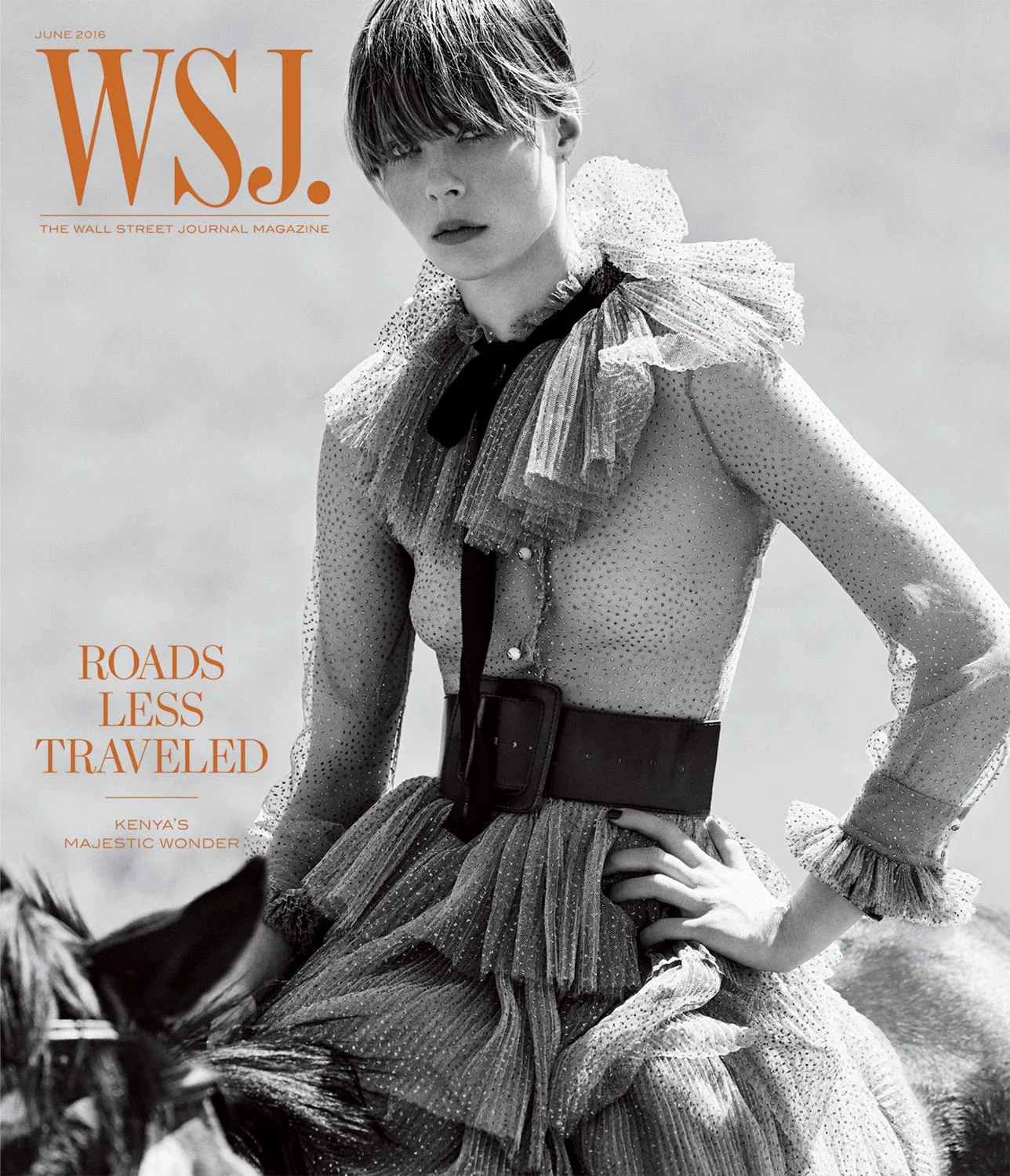

Calvin Cottar's 1920s Kenya Conservation Camp With Anna Ewers + Edie Campbell By Mikael Jansson

/Top models Anna Ewers + Edie Campbell are styled by George Cortina in ‘Great Explorations in Kenya’, lensed by Mikael Jansson for WSJ Magazine June 2016.

The shoot took place at Cottar’s 1920s Camp in Kenya, a private conservancy with an innovative approach to protecting the area’s natural biodiversity, wrote Tom Downey for WSJ Magazine. Located in a corner of Kenya, just southeast of the Maasai Mara National Reserve, the camp has a comparatively unique history.

Calvin Cottar is one of East Africa's most renowned private guides and part of a family has been running safaris in Kenya for 90 years. Unlike the vast majority of white safari operators in Africa, the Cottar family did not settle in Africa as Europeans. Calvin’s great-grandfather Chas Cottar moved to Kenya from Oklahoma after reading Teddy Roosevelt’s book ‘Game Trails of Africa’ in 1909.

In 1919 the elder Cottar set up his own safari outfitting and guiding business "Cottars Safari Service," the oldest safari outfitting company in Africa. Ninety years later, 4th generation Kenyan, Calvin Cottar and his family seek to replicate those historic, legendary experiences with modern updates.

“I want to give visitors here the same experience I had growing up in the bush,” Cottar says. “We don’t hunt animals as we did then, but 99 percent of what we did back then was the walk leading up to the kill.”

“This isn’t the place you come to check boxes, to show you’ve seen all the big game from a car,” Cottar says. “This is where you come for experiences that make you part of the natural world. When we track animals, we’re not just observers. We become part of their story.”

Based on his family’s long relationship with Kenya, the Cottar family is looking towards the future. “So much of what you hear about Africa in America or Europe is these evil criminals poaching elephants or rhinos,” Cottar says back at the tent camp. “And of course there is some of that. But the far greater long-term challenge here is land use: The Maasai need land to feed their cattle and goats.”

Being committed to writing with clear heads about Africa at GlamTribal and Anne of Carversville, we are making every effort to spend even more hours writing about the intersections of people and animals in Africa and not only the perils of poaching.

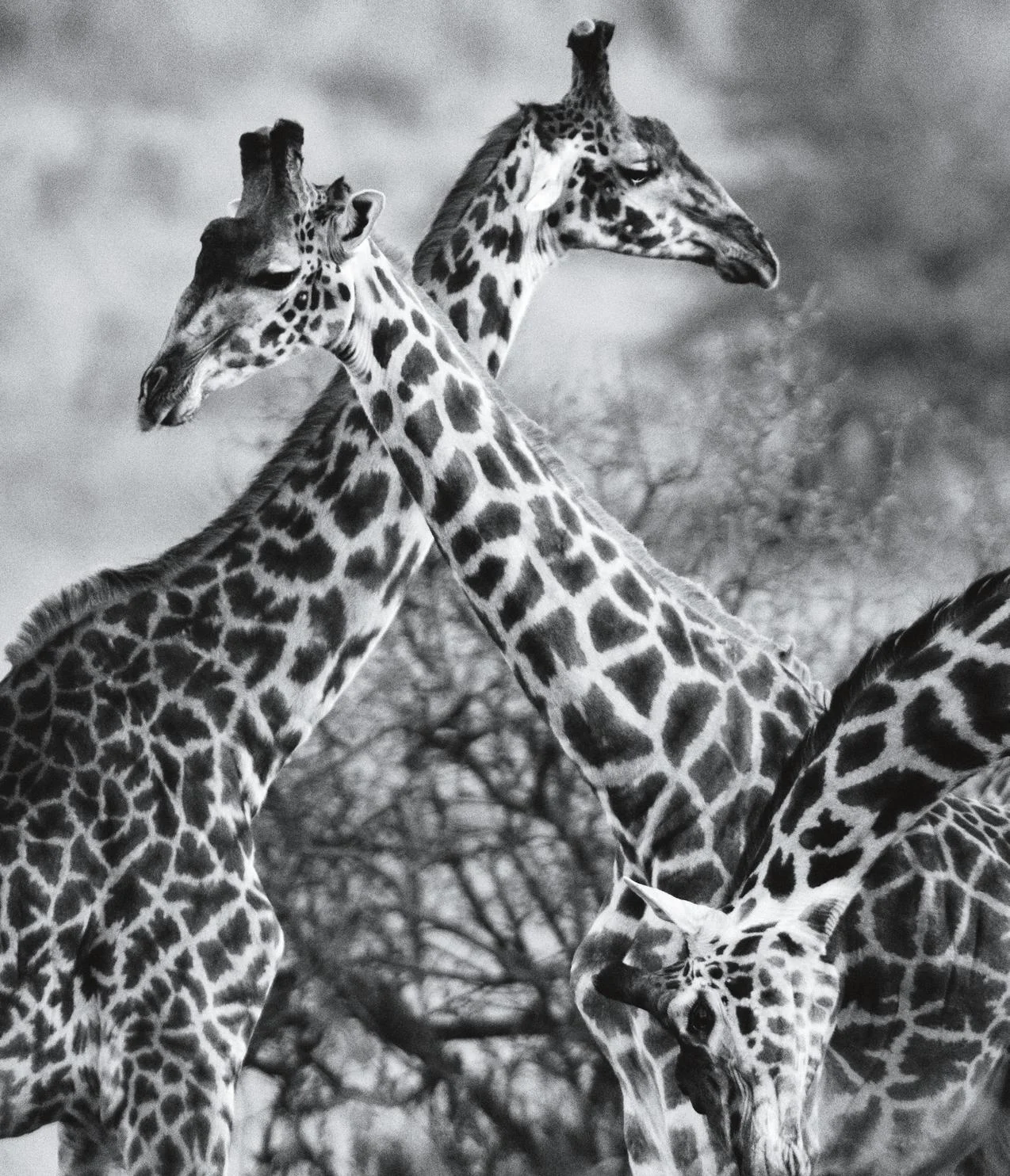

Cottar’s Camp looks down across the valley toward grasslands that stretch into Tanzania’s Serengeti plains, just a few miles away. (See it on the map at the very southern point in green). Baboons and monkeys mix with antelopes and zebras—as well as a tiny, orphaned Thomson’s gazelle (christened Bambi) being raised by a Maasai named Charles.

“Wildlife takes a lot from the land,” Cottar continues. “If we want to protect these areas, we need to make it worthwhile for the locals who live here to graze their cattle somewhere else. If we don’t, they’ll keep killing wildlife in order to survive. And how can anyone blame them for doing that if it’s the only way they know how to live?”

Cottar continues his Western education of international visitors about nature parks and concessions in Kenya. In 1998 he built this permanent camp on a small concession obtained with the permission of the Maasai, whose population has doubled in Kenya over the past 30 years.

“At the national parks, like the one just down the road,” says Cottar, “the money goes to the government, not to the people who have traditionally lived on the land. I want to change that by directly paying the people who live here to rent the land from them and penalizing them, collectively, when people in their community poach from their land.”

At the time of his WSJ Magazine interview, Cottar concluded a long-time negotiation a group of Maasai who own and inhabit the land around his camp. The Maasai want to be closer to town and Cottar wants wildlife, not cattle, on the land.

It should be stated that Cottar is not opposed to controlled trophy hunting as a conservation model. Given the reality that Kenya outlawed trophy hunting in 1977, the conservationist sees only one major way forward: “Ideally it wouldn’t just be Cottar’s Camp, it would be all the developed nations of the world agreeing to help pay local people in order to rent their land.”

The week after writer Tom Downey left Kenya, “Cottar boarded a plane for the Save Wildlife conference in The Hague, tasked with trying to persuade global conservation leaders that the best way to save Africa’s natural biodiversity is to implement on a large scale what he’s managed to do at Cottar’s Camp: deal directly with the people who live on, and rightfully own, the land and animals that will vanish without greater protections. “

Calvin Cottar has a January 2019 update on this challenge of how to secure the future of Africa’s Wildlife. After researching it and related materials, AOC will offer our own summary of the situation around Cottar’s international vision for wildlife management in Kenya and beyond.