MacKenzie Scott's HBCU Giving Contrasts Starkly With Historical White Funders

/By Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Associate Professor of Philanthropic Studies, Director of Undergraduate Programs, Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, IUPUI. First published on The Conversation

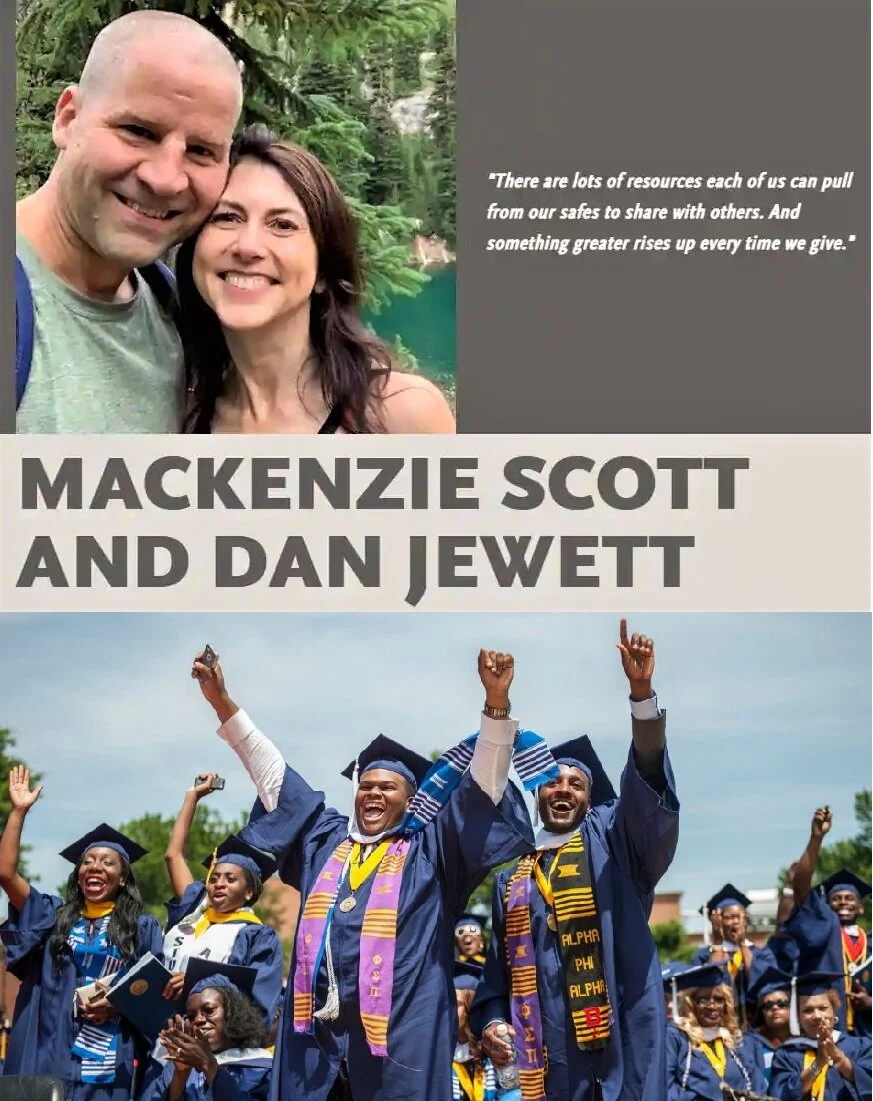

Novelist and billionaire philanthropist MacKenzie Scott has so far given at least US$560 million to 23 historically Black colleges and universities. These donations are part of a bid she announced in 2019 to quickly dedicate most of her fortune to charity.

Scott’s gifts, including the $6 million she donated to Tougaloo College in Mississippi and the $45 million she gave North Carolina A&T University, vary in size but nearly all of the colleges and universities describe this funding as “historic.” For many, it was the largest single donation they had ever received from an individual donor.

Scott, previously married to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is not making a splash just because of the size of her donations. She has an unusually unrestrictive get-out-of-the-way approach.

“I gave each a contribution and encouraged them to spend it on whatever they believe best serves their efforts,” Scott wrote in a July 2020 blog post.

She sees the standard requirements that universities and other organizations report to funders on their progress as burdensome distractions. Instead of negotiating detailed agreements before making a gift, she works with a team of advisers to stealthily vet a wide array of nonprofits, colleges and universities from afar before surprising them with her unprecedented multimillion-dollar gifts that come without any strings attached.

Scott is also supporting students of color through donations to the United Negro College Fund and the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, which give HBCU students scholarships, and by supporting many other colleges and universities that enroll large numbers of minority students.

Her approach sharply contrasts with how many wealthy white donors have interacted with Black-serving nonprofits, including HBCUs, in the past. As a historian of philanthropy, I have studied the paternalism of white funders, including those who helped many of these schools open their doors.

HBCU Origins

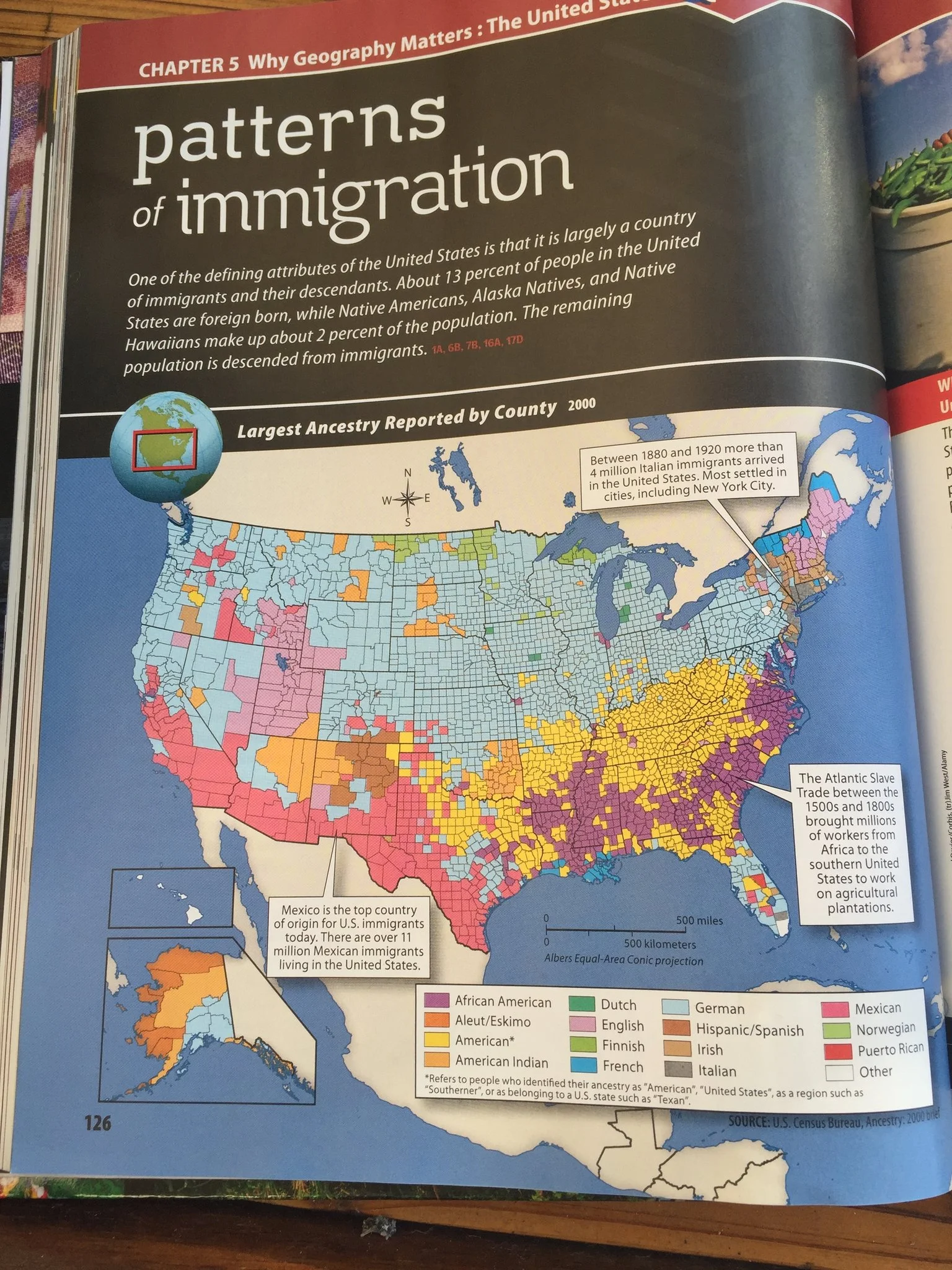

The first HBCUs were founded in Northern states before the Civil War, including Cheyney and Lincoln universities in Pennsylvania and Wilberforce University in Ohio. After the war, most HBCUs were established in Southern states. These institutions were lifelines for Black Americans seeking higher education during decades of Jim Crow segregation that locked them out of other colleges and universities. (Disclosure: I earned my bachelor’s degree at Lincoln University.)

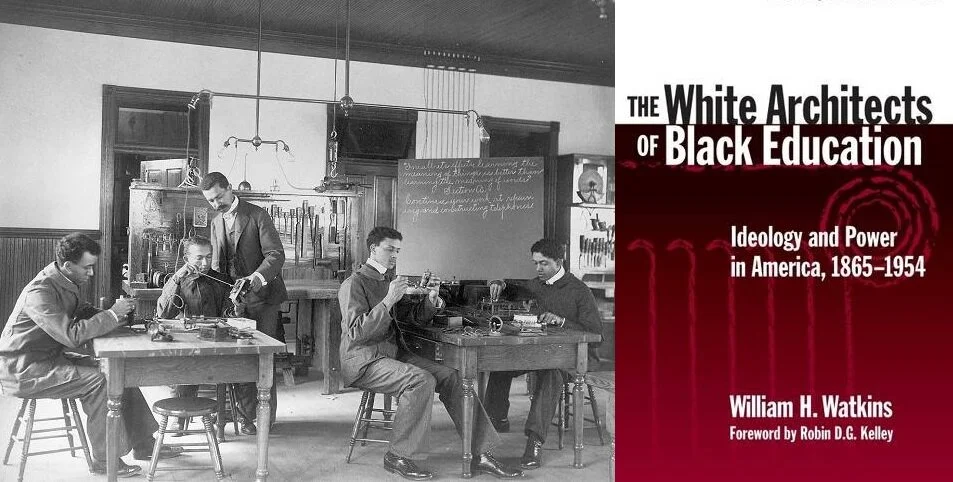

Although many white philanthropists made large gifts to these schools, their support was fraught with prejudice. Initially, white funders pushed for HBCUs to emphasize vocational training, then called “industrial education,” such as blacksmithing, printing and shoemaking, over more intellectual pursuits.

White philanthropists including Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller had poured millions from their fortunes into the proliferation of Black industrial schools by the early 20th century. The HBCUs Hampton University in Virginia and Tuskegee University in Alabama, which received donations from Scott, were leading models of industrial education for decades.

The vocational curriculum at these schools was promoted as preparing Black students to be skilled laborers and academic teachers. During this era, however, most graduates worked as unskilled laborers or vocational teachers.

White Southerners overwhelmingly approved of this arrangement, which left many HBCU grads on the bottom rung of society rather than making them educated citizens. Emphasizing industrial education at HBCUs preserved the superior economic status of white Americans and the racist system of segregation. But African Americans’ educational aspirations required much more.

W.E.B. Du Bois, a prominent Black intellectual, was a leading critic of the funding HBCUs got from wealthy whites. He said: “Education is not and should not be a private philanthropy; it is a public service and whenever it merely becomes a gift of the rich it is in danger.”

In 1904, the HBCU leader Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of Florida’s Daytona Normal and Industrial School for Negro Girls – now Bethune Cookman University – felt this pressure. She placed “industrial” in her school’s name to attract white funding. But she sought to give Black students a liberal arts education that she believed would support their full citizenship.

Decades later, the sociologist Charles S. Johnson served as Fisk University’s first Black president, starting in 1946. He sought to turn that Tennessee HBCU, founded in 1866, into a powerhouse of Black liberal arts education in partnership with white philanthropists and foundations rather than covertly.

HBCU leaders have, in short, faced a predicament for generations: When rich white donors offer big donations, can the money truly be used to support Black educational interests and goals?

Prejudiced Backlash

When HBCUs secured funding early on, that money was often jeopardized because of bigotry.

In 1887, for example, the Georgia state Legislature withdrew $8,000, worth approximately $220,000 today, in critical annual funding from Atlanta University. The HBCU, founded in 1865, had flouted Southern norms by allowing whites and Blacks to share campus facilities, which white politicians did not appreciate.

Later, the school embraced a liberal arts curriculum, bucking the more vocational emphasis white segregationists preferred.

In response, many white philanthropists withdrew their donations.

Despite that challenge, Atlanta University persevered, eventually merging with Clark College. And so it is historically significant that Scott gave Clark Atlanta University $15 million in 2020 to use as it sees fit. The school is using the money for academic innovation, infrastructure and scholarships, and to build up its endowment.

Undercutting Black Medical Schools

In 1908 there were seven Black medical schools in the U.S. By 1921, following a sustained attack on those institutions, only two remained: Meharry Medical College in Nashville and Howard University in Washington, D.C.

The loss of those schools began in 1910, when Andrew Carnegie’s foundation funded a report by educator Abraham Flexner. Part of a larger reform movement to standardize medical training, Flexner’s study recommended the closure of five Black medical schools. It led white funders to sever their support.

At the time, there were extensive problems with medical education across the board in the U.S. There were no standards for curriculum or instruction. But Black medical schools’ particular problems – poor funding, insufficient faculty and inadequate facilities – were exacerbated by Jim Crow segregation and condescension from the establishment.

Flexner’s site visits were incredibly short. He castigated Black doctors as a group without interviewing them. He recommended support for Meharry and Howard to ensure that at least some Black doctors would be able to care for Black patients in segregated hospitals and prevent the spread of disease to the white population.

Carnegie’s and Rockefeller’s foundations were initially reluctant to support the two surviving medical schools in implementing Flexner’s suggested reforms. Their subsequent funding ebbed and flowed irregularly. Scholars have estimated that the Black medical schools closed after Flexner’s damning report would have produced 35,000 Black doctors over the past century.

For decades HBCUs such as Xavier University in Louisiana, which received $20 million from Scott in 2020, have been top producers of Black graduates who become doctors.

A Continuing Problem

A long-term shortage of Black doctors remains a critical public health issue today, reflecting the sustained underfunding of HBCUs.

For example, Maryland’s HBCUs won a settlement against the state in 2021 totaling $577 million intended to remedy decades of underfunding compared with the state’s predominantly white colleges and universities.

Scott funded three of those public institutions: Bowie State, Morgan State and University of Maryland Eastern Shore in 2020.

A review completed in 2021 of Tennessee State University, another HBCU, found the state underfunded it by an estimated $544 million compared with the school’s white counterparts, dating back to 1950.

HBCUs Today

Today there are about 100 HBCUs, half of which are public institutions. They enroll roughly 300,000 students and award nearly 50,000 degrees annually.

Seventy percent of HBCU students are eligible for Pell grants, making the schools critical for first-generation and low-income students. Although they represent only 3% of all degree-granting institutions, HBCUs confer 13% of all bachelor’s degrees earned by Black Americans.

Today, a disproportionate share of HBCU grads become doctors – making these schools a vital on-ramp into the middle class for students of color.

And yet HBCUs are financially fragile. The 10 largest HBCU endowments total $2 billion, just 1% of the $200 billion held collectively by the 10 predominantly white colleges and universities with the largest endowments.

Despite the financial challenges these schools have faced, HBCU graduates include some of America’s most prominent figures, including Martin Luther King Jr., Vice President Kamala Harris, multimedia mogul Oprah Winfrey, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, filmmaker Spike Lee and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison.

There’s no way to know the full toll endured by HBCUs and the Black community as a whole from long-term underfunding and donor hostility. In my view, it will take decades of Scott-style giving for HBCUs to recover what has been lost in time, compound interest and impact over generations.