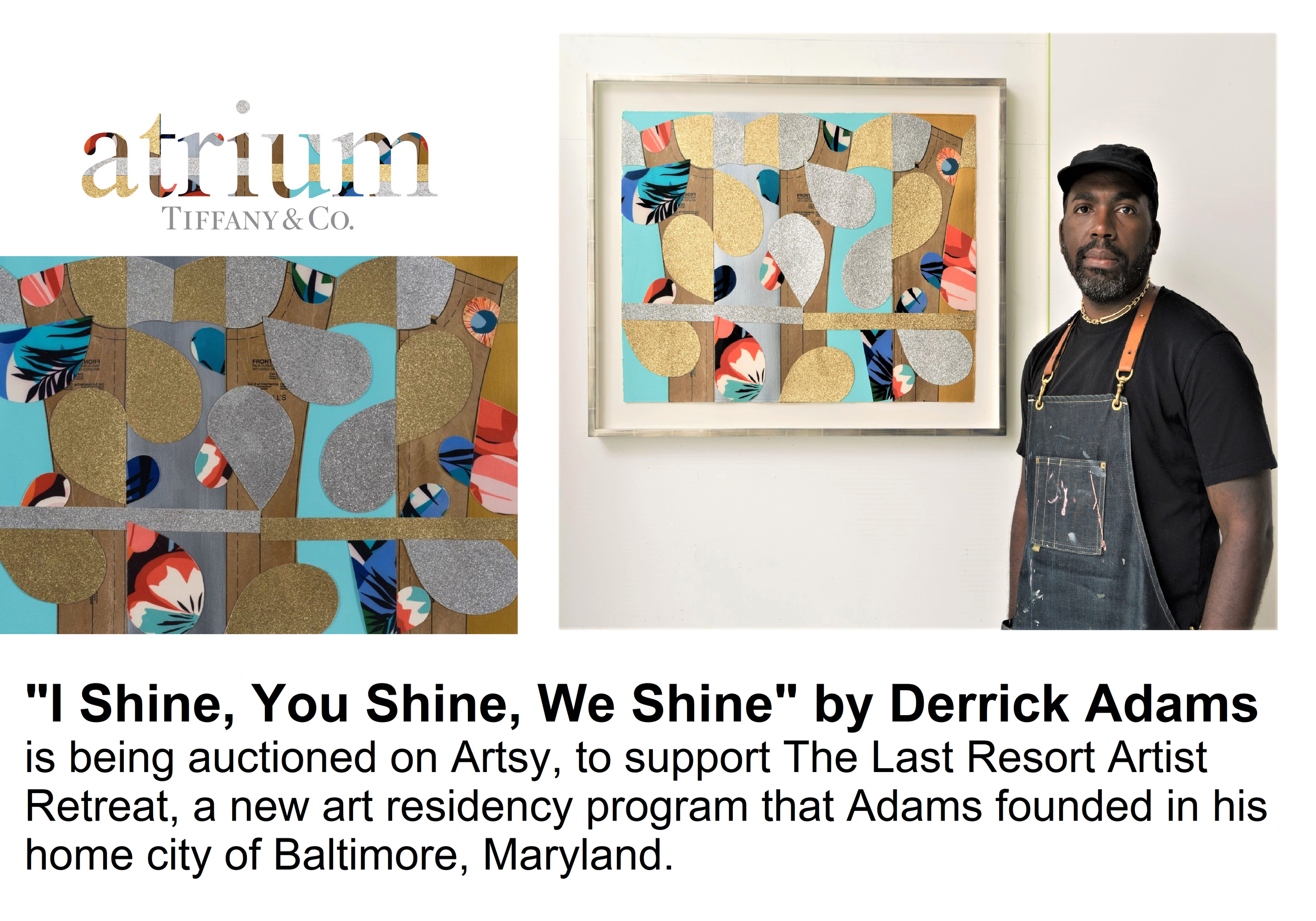

Tiffany Atrium Supports Derrick Adams' The Last Resort Artists Retreat in Baltimore

/Creating Tiffany Atrium

Tiffany & Co. has introduced Tiffany Atrium, a social impact platform that advances opportunities for historically underrepresented communities in the fine jewelry and creative fields. Tiffany’s parent company LVMH has taken a strong position on its change-agent obligations in a post-George Floyd world.

Many companies in the fashion and design industry have accepted the challenge of increasing the numbers of diverse creatives and artisans in its ranks. The LVMH luxury brands are big leaders in this initiative and Tiffany & Co is perfectly positioned to carry this mantle forward with purpose and agency, having championed key initiatives like animal conservation and ethical jewelry making for years.

Tiffany & Co. understands that this work requires commitment, leadership, and learning—all of which is reflected in Atrium’s three core pillars: creativity, education and community.

Enter Derrick Adams and Everette Taylor

L-R: Artist Derrick Adams, Artsy CMO Everette Taylor, at Tiffany Atrium x Artsy Launch Breakfast. DARIAN DICIANNO/BFA.COM via Forbes.

Seeking to help supporters and Tiffany & Co. clients visualize the new Atrium concept, the iconic American jeweler reached out to artist Derrick Adams, who created an original artwork called “I Shine, You Shine, We Shine” for the Atrium launch.

Derrick Adams’ work reflects how people of African descent interact with art, American history and consumerism. “I shine, You shine, We Shine” will be auctioned by online art shopping platform Artsy until August 10. The current bid for the artwork is $40,000 against an estimate of $50,000 to $70,000.

In late July well-heeled guests enjoyed Bellinis and caviar-crested canapés in a real-life ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’. Forbes profiled the breakfast, in which Adams was joined by Artsy CMO Everette Taylor, to discuss the inspiration for his artwork, collaboration with Tiffany & Co., and expanding opportunities for underrepresented communities.

“It's very important for brands and artists to work together especially if you're doing things that can benefit communities that are not getting as much exposure and enough shine,” Adams said this morning in a conversation with Artsy CMO Everette Taylor. “Helping other people does not take away from helping yourself. The idea (is) that a brand like Tiffany, working with artists like myself, can actually bring awareness to the importance of supporting communities that are not necessarily considered in certain aspects like design. When you think about design, who's designing things, you don't see a lot of Black people as a center. I think that having me here and having me talk about these things and having me work with Artsy or with Tiffany is a great collaboration. I think it's probably the beginning of many more with artists working with Tiffany and Artsy, because I think that these types of collaborations, a crossover with different brands working together, is a great model to really support communities, communities that have creativity, communities that are thriving creativity, but lacking an opportunity.”

The Last Resort Artist Retreat in Baltimore

100% of profits from the sale of “I Shine, You Shine, We Shine’ are going to The Last Resort Artist Retreat [IG] an art residency program that Adams founded in his home city of Baltimore, Maryland, with the goal of providing support, community and invigorating creative refuge to African-American artists and cultural workers.

Read more about the project in Baltimore Magazine: Derrick Adams to Launch a Visionary Archive in Waverly.

The project is slated to welcome its first month-long residents from the Black creative community to his hometown of Baltimore in March of 2023. Surface Magazine also spoke with Adams and Taylor at the Atrium launch breakfast and highlighted information about TLRAR.

Adams says the bed and breakfast-style residence in Baltimore’s historic Waverly neighborhood has already hosted dinner parties with historians, visual artists, culinary artists, and musicians to begin cultivating more connections within the city’s creative community. “That’s our focus: to think about leisure as a therapeutic practice, to really think about people who experience oppressive structures that are built to keep people out, to think about joy, or think about the idea of leisure within the turmoil that we experience constantly. It is a political act for me, to put this face into existence, and for people to come and unwind,” says Adams.

Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation on Artsy

As the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, who founded Tiffany & Co. in 1837, Louis Comfort Tiffany ushered in a new era at the famous jeweler as the house’s first art director.

One of America's most celebrated artists, Louis Comfort Tiffany revolutionized the production of stained glass and incorporated it into innovative designs and unusual decorative items. This served to reinvigorate an industry that had barely changed since the Medieval Period.

The artist had convented his summer mansion in Cold Spring Harbor in Long Island into an artists’ residency in 1918, when Tiffany established the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, the first organization of its kind in the United States.

Today, the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation is very active on Artsy and their own Biennial Grants reward 20 artists with $20,000 stipends for which the artists have not applied. More than 500 American artists have benefitted from the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation since the first awards launched in 1980.

How fitting that the foundation is now involved with Artsy and tangentially — if not directly — involved in supporting The Last Resort Artist Retreat in Baltimore. A fire destroyed Laurelton Hall in 1957, when it was in a state of disuse.

In 2018, the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation celebrated its centennial anniversary, making it the oldest artist-endowed foundation in America, and the first to have been founded by a living artist.