After Warren Kanders Resignation From Whitney, Museum Boards Ponder Their Futures

/Last week ended on a positive note for protesters and artists committed to forcing the resignation of Warren B. Kanders as vice chair of the board of New York’s Whitney Museum.

Protesters were adamant that his ownership of Safariland, a defense-manufacturing company that supplied state-of-the-art tear gas to quell protesters everywhere in the world disqualified him as any kind of representative of artists opposed to global militarization. Evidence mounted that Kanders’ stake in Sierra Bullets,linked him directly to high-velocity ammunition allegedly used by Israeli soldiers in Gaza against Palestinian civilian protesters.

With Kanders out at the Whitney and no specified game plan on how to move forward, all parties involved from artists to activists, patrons and buyers of art are asking what happens next. ARTnews writes that the Kanders’ resignation is a sign “of the shifting balance between museum boards and their critics, with protesters believing that they have won the day.

Don’t overthink the situation, say many of the critics, who have generally taken a stand against defense contractors and fortunes made from armaments worldwide. The Sackler family also has been the target of protests as they are tied deeply — if not exclusively — as profiteers tied to America’s epidemic drug crisis launched by OxyContin.

Image of Whitney protests via ARTNews.

Among the artists at the Whitney Biennial who best symbolized the contradictions for artists involved in the conflict was San Juan–based artist Nibia Pastrana Santiago. was not among the eight artists who had withdrawn from the Whitney Biennial. But she was among the citizens of Puerto Rican citizens who protested the official residence of Puerto Rico’s then Governor Ricardo Rosselló, before he also resigned at week’s end.

“I couldn’t breathe, my eyes are burning, we were following each other…running and holding strangers hands…’cause you can’t see,” Santiago told artnet News of the impact of the tear gas. “I felt like drowning, I felt like fainting. Fortunately there were colleagues with remedies. Once I caught my senses again, ’cause really the gasses disorient you, we went back to the line.”

The artists explained that the protests were all peaceful and she was stunned to see tear gas used. She had no way of knowing if Kanders’ company Safariland had manufactured the tear gas or not, although both Hyperallergic and the Nation argue for a connection.

From his point of view Kanders argued that it was his job to manufacture the tear gas for law enforcement agencies, not determine the ethics of situations in which it was used.

Speaking about the Kanders resignation, Adam D. Weinberg, the Whitney’s director, said: “Here’s a man who has given a tremendous amount of his time and money to young, often edgy and radical artists — somebody who is very progressive — that’s one of the ironies of all this.” Weinberg continued:

“The Whitney Museum is one of the most progressive, the most diverse, the most engaged, open programs of any major institution in the country,” Mr. Weinberg added. “Every museum director is looking at us right now and saying, ‘Gee, if the Whitney is being targeted, what’s going to happen to us?’”

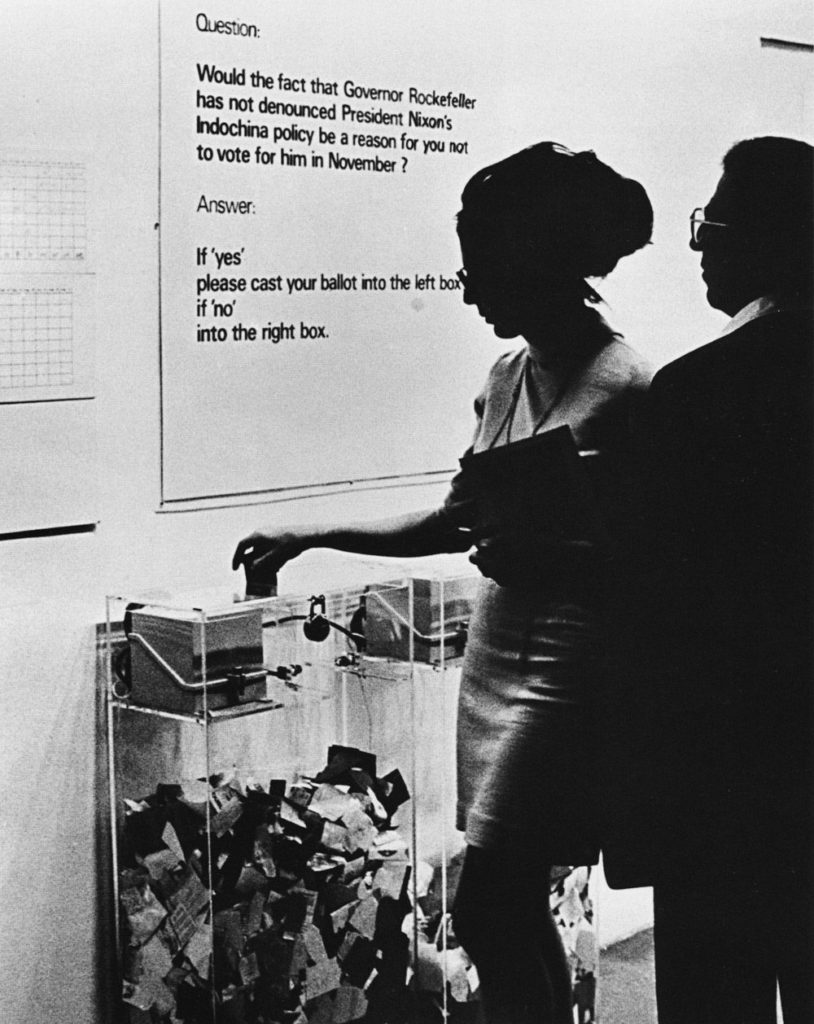

artnet reminds us that conflicts about museum boards are hardly new, sharing this 1969 image from the Guerrilla Art Action Group, who protested then-MOMA trustee Nelson Rockefeller’s ties to weapons used in the Vietnam War.

The conflicts that exist on museum boards are not found in other institutions, also reliant on donations. A donor to Harvard clearly get his or her name on a building or lecture hall. The university president will surely take a call from a big donor without delay, and children and grandchildren are given preferential treatment. But donors aren’t sitting on the governing board of the university in most cases. Professionals with expertise run those institutions.

In art museums, donors serve as the institution’s primary governing body, the reward of making major donations. One can argue that their own art investments can increase in value through their efforts in planning museum shows and making and breaking certain artists. These same donors are also charged with policing the very institutions they are governing — which is an impossible ethical situation, say critics.

After researching the 2016 US elections and publishing ‘Museums, Money, and Politics’, artist Andrea Fraser wrote that her project “developed out of my personal sense of horror at discovering supporters of radical right-wing politicians serving on the boards of arts organizations with which I work and whose missions are directly threatened by the policies these politicians advance.”

Fraser asks why museums should be governed by donors, when there is no good reason. artnet writes:

Such a shift, she (Fraser) says, would also make museums more aligned with other fields, like medicine, science, social services, and education, where board members are selected based on professional expertise, scholarship, and their ability to further the institution’s mission. “The arts appear to be at the extreme of prioritizing wealth over all other criteria,” she notes. “It is easy to see how major decisions like the hiring of directors and architects are impacted in many museums by the lack of a range of stakeholders on boards.”