Wild Bee Populations -- Different Than Honeybees -- Are Devastated By Pesticides

/A Common Soil Pesticide Cut Wild Bee Reproduction by 89% and Scientists Are Worried AOC Sustainability

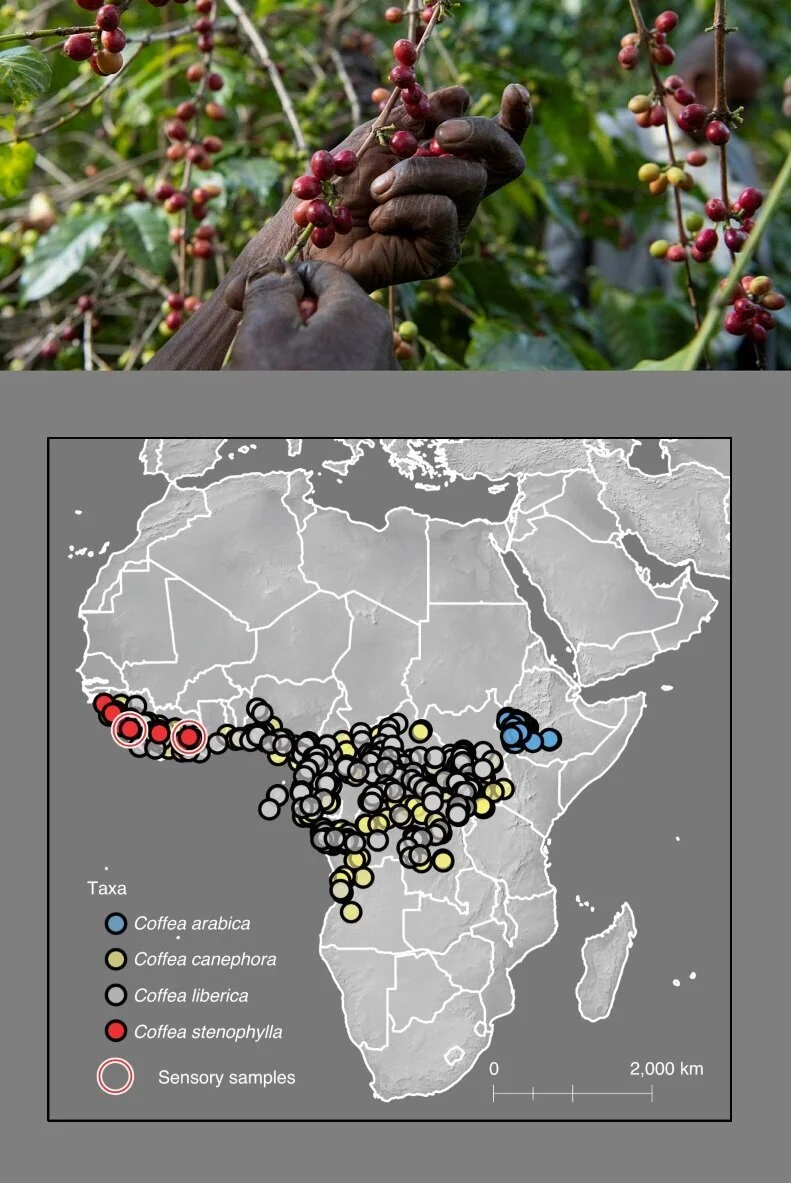

Most of the world’s 20,000 bee species don’t live in hives. These wild species lead comparatively solitary lives , with large majorities building their nests underground where they raise their offspring on the nectar they gather from flowers.

Considering the general state of alarm about the health of bees generally and colony collapse disorder specifically, how can it be that the vast majority of research on the impact of the neonicotinoids family of pesticides has been done only on honeybees and now bumblebees?

Because honeybees don’t spend much time on the ground, environmental risk assessments for neonicotinoids often neglect to consider how exposure to these chemicals in the soil affects all pollinators. But in a landmark study published in Nature, researchers have shown how neonicotinoids affect bees not just by accumulating in the plants pollinators visit, but in the ground where most wild bees build their nests.

The researchers studied nest building, foraging and reproduction in these bees and found imidacloprid in particular – one of the most widely used neonicotinoids worldwide – had a devastating effect on all aspects of squash bee life. Compared to insects living on untreated cropland, the hoary squash bees exposed to imidacloprid in the soil created 85% fewer nests, left 5.3 times more pollen unharvested and produced a staggering 89% fewer offspring.