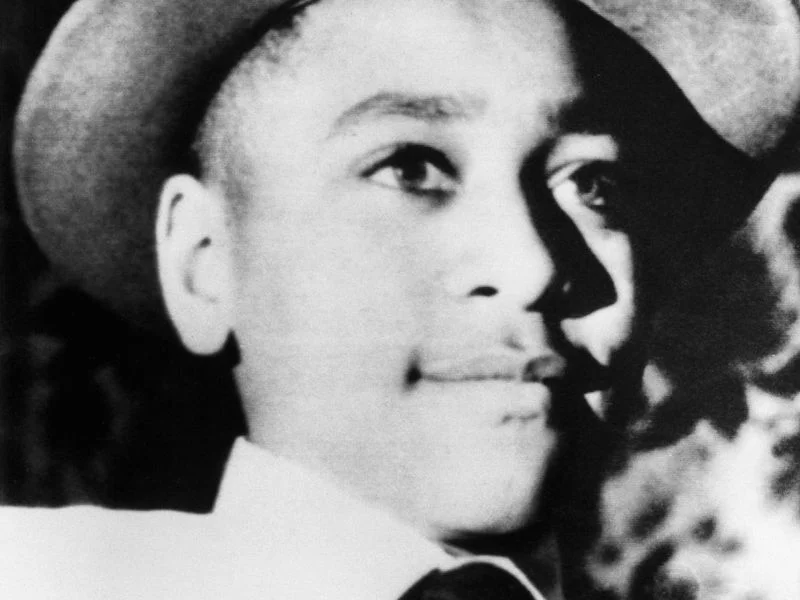

Emmett Till Memorial to Be Replaced With Bulletproof Sign Due to Repeated Vandalism

/By Brigit Katz. First published on Smithsonian.com.

In 2007, a sign was erected along the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi, marking the spot where the body of Emmett Till was pulled from the water in 1955. The murder of Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy who was brutally killed by two white men, became a galvanizing incident of the Civil Rights Movement. But over the years, the memorial commemorating his death has been repeatedly vandalized—first stolen, then shot at, then shot at again, according to Nicole Chavez, Martin Savidge and Devon M. Sayers of CNN. Now, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission is planning to replace the damaged memorial with a bulletproof sign.

This will be the fourth sign that the commission has placed at the site. The first was swiped in 2008, and no arrests were ever made in connection with the incident. The replacement marker was vandalized with bullets, more than 100 rounds over the course of several years. Just 35 days after it was erected in 2018, the third sign was shot at as well.

The third memorial made headlines recently when Jerry Mitchell of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, in conjunction with ProPublica, revealed that three University of Mississippi students had been suspended from their fraternity house after posing in front of the sign with guns, in a photo that was posted to the private Instagram account of one of the students. The Justice Department is reportedly investigating the incident.

The sign has now been taken down, and a new one is “on its way,” Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, said last week, according to CBS News. Chavez, Savidge and Sayers of CNN report that the replacement memorial will weigh 600 pounds and be made of reinforced steel. It is expected to go up by the Tallahatchie River in October.

“Unlike the first three signs, this sign calls attention to the vandalism itself,” the commission noted. “We believe it is important to keep a sign at this historic site, but we don’t want to hide the legacy of racism by constantly replacing broken signs. The commission hopes this sign will endure, and that it will continue to spark conversations about Till, history, and racial justice.”

Till, a native of Chicago, was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he had a fateful encounter with a white woman named Carolyn Bryant, who claimed the teenager had flirted with her. The woman’s husband and brother subsequently kidnapped Till, beat him viciously, shot him in the head and threw him into the Tallahatchie River. His body was so disfigured that when it was found three days later, it could only be identified by Till’s signet ring. At Till’s funeral, his mother decided to leave the casket open, bearing witness to the brutal racism that had killed her son. Photos of Till’s mangled body, published in Jet magazine, gave rise to a generation of Civil Rights activists.

The men who killed Till, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, were put on trial for the crime. They were found not guilty by an all-white jury.

As part of its efforts to keep Till’s story ever-present in the public consciousness, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission is planning a number of initiatives. The group is, for instance, working with a local landowner to develop Graball Landing, the riverside location where Till’s body was recovered, into a “site of conscience”—with a security gate and cameras. A website and mobile app that will let users explore important sites in Till’s story are also in the works. The team is additionally lobbying for the establishment of a “Mamie and Emmett Till National Park.”

But a pressing priority is to get a reinforced Till memorial back up along the Tallahatchie River.

“We won’t stop. There will be another sign up," Reverend Willie Williams, the commission’s treasurer, tells CNN. “This particular area will go forward in the long run. Because this legacy and this story, it's much bigger than any of us.”