"Isolated" Societies, a Tourist Fantasy and Bringing Jesus to Their Inhabitants

/By Aurélie Condevaux, Anthropologist University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. First published on The Conversation.

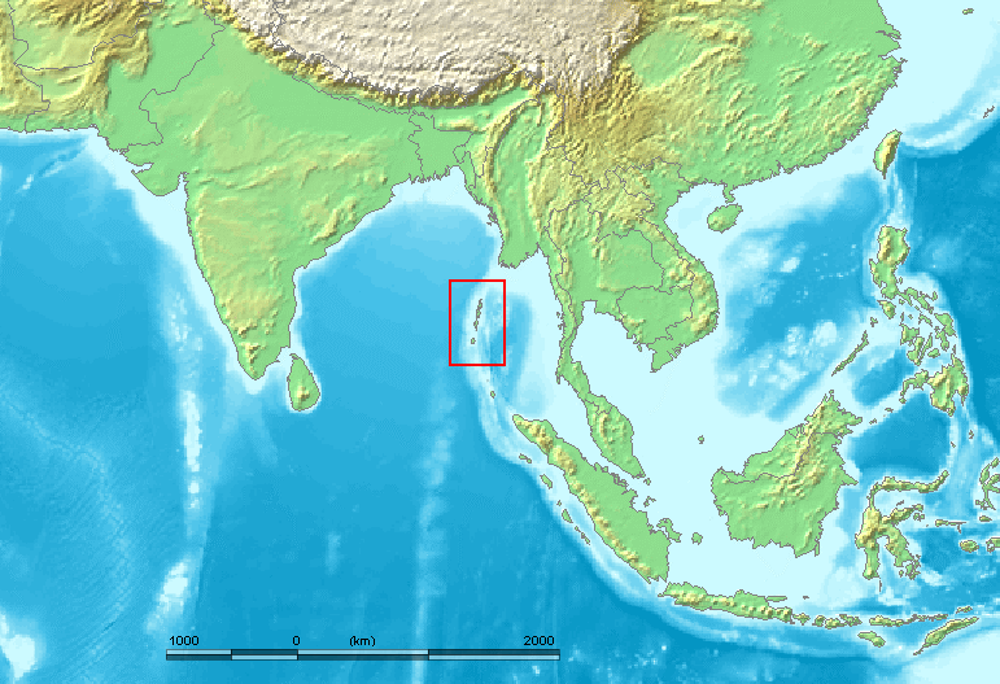

In November 2018, John Chau was killed in the Andaman Islands, wanting to access the island of Nord-Sentinel for, he said, "bring Jesus" to its inhabitants.

In the same archipelago, on the southern and central Andaman Islands, the Jarawa are in a situation almost opposite to that of the Sentinels, known to live in complete isolation.

There, on the other hand, attempts to ban the presence of tourists - regarded as carriers of an unhealthy curiosity and harmful influences - are more or less total failure since they have access to island communities and behave with them. like the Europeans of XIX th century during the colonial exhibitions even throwing them bananas .

Western imaginaries that endure

The media treatment of the first case, and the forms of tourism that exist among the Jarawa , tell us in particular about the representations firmly anchored in the Western imaginary on certain types of societies considered as "apart" (we will see in what way), and the relationship to "others" that any society has.

These cases have, moreover, raised controversies whose central object is the appropriateness or otherwise of the behavior of foreigners - in this case missionary or tourists - in societies where they have not been invited. In response to the death of John Chau, the director Aruna HarPrasad exclaimed:

"But who was this young man, and who we are, to arrogate to us the right to disturb these people and corrupt these isolated tribes living in harmony with a nature we have now forgotten? even essence? "

How can social scientists answer this question and how do they position themselves in relation to the ethical questions raised by these "contacts" and the development of tourism in "isolated" societies?

Companies out of time?

The vocabulary used in the media to describe the Sentinels or Jarawa, two indigenous groups (in the sense of first inhabitants) of the Andaman Islands, is, in many ways, dated: the first are called "people" or "isolated people" , a "tribe considered the most isolated on the planet" who "has been living in autarky for centuries" .

In the same way the Jarawa are considered as "an isolated tribe that is just beginning to come into contact with the outside world", whose history "goes back to the dawn of time", since they are "from the first migrations of Africa And as such would be even "Pygmies" .

The semantic field used is not insignificant: placed away from the rest of humanity by the use of a specific terminology ("peoples" rather than "society" for example) and the suggestion of a stage of development more "primitive", these societies undergo a form of differentiation, which is also hierarchical. Without stopping on this question, let us simply say that this vision corresponds to long-standing ideas, since these societies are contemporary - their history goes back no more or less to the mists of time than that of others - and have " evolved "like the others .

A largely exaggerated isolation

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Photo by Pau Casals on Unsplash

In addition, there is no need to be a specialist in this area to understand that if the contacts of the residents of the North Sentinel Island with people who do not reside there are indeed weak, give the impression that these companies have remained in near total isolation until recent years is largely exaggerated.

Apart from exchanges between indigenous societies within the Andaman Islands themselves, contacts exist with other groups. The archipelago did not escape the colonial rule: between 1858 and 1900, a British-Indian penitentiary system was established there.

The inhabitants of the Andaman, represented even before being known as being among the most "primitive" peoples , become at this moment objects of photography, of "scientific" study, even of "desire", that it is necessary " domesticate "; in short, they are widely "contacted".

In the XXI th century, although ephemeral, the contacts extend .

The staging of the so-called "first contacts"

The media outbursts on the isolation of the Sentinels and Jarawa is thus one more example in a long series of staged so-called "first contacts" that seem to play again and again in different parts of the planet.

As Pierre Lemonnier points out in Papua New Guinea these societies are presented as traces of a "stone age" , and the journey to reach them as a journey back in time.

In these different cases, the fact that some societies have had tenuous contacts with representatives of their national administration and even more with the "Western world", do not make them "lost tribes" who would ignore the outside world, and let alone the living testimonies of dead human organizations.

Misunderstandings of the meeting

We can not therefore be content to explain what happened in the death of the young American, and in the tourist interactions with the Jarawa, as part of an ignorant - but also "hostile", "aggressive" rejection - of the "other" in the first case, or the opposite of a fascination with "foreigners and what they have to offer" in the second case. On the contrary, it should be explained in the continuity of older exchanges.

As the anthropologist Gerard Lenclud writes in an article in the journal Gradhiva (1991, "The world according to Sahlins") "any encounter between human beings, calls at once and on each side the connection between what is perceived and a symbolic system.

In other words, everyone is brought to relate the unknown to something more familiar so that it "makes sense". These interpretations, it is easy to imagine, are likely to generate misunderstandings, which stem from the divergent meanings that can be given on both sides to the same situation.

A question of interpretation

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India.. Photo by Himanshu Jariyal on Unsplash

In the case of the Sentinels and Jarawa, the interpretations of - and thus reactions to - the arrival of foreigners would be understood according to two key points. On the one hand, the status and representations of these in society and on the other hand, the interactions that have occurred in the past with other foreigners.

However, almost nothing is known about the first point, and therefore we can not understand how the Sentinels perceived the young missionary arriving on their beach, and the "misunderstanding" that could be played out there.

On the other hand, we know a little more about the representations that allow the tourists or the missionary to "make sense" of their meetings: for the first, the Jarawa are an "isolated people", which is more relict of the societies of homo sapiens out of Africa 60,000 years ago.

For the second, they are in addition pagans that would have to come out of ignorance and sin. To see them this way may partly explain (but not excuse) that we allow ourselves to ask a woman to dance for herself, to take forbidden pictures, or even to throw food through the window of cars, or that we can set foot on a beach thinking to be authorized and protected by a divine mission.

Tourism in Aboriginal societies

Note that no one escapes the categorical assignments and misunderstandings of the meeting. The foreigner - whether missionary, tourist, anthropologist or other (the nuances we make between these categories sometimes have little meaning for those they meet ) - is always assigned an identity by the society he wants study, evangelize or visit.

Conversely he or she thinks the "other" according to a reference system of his own. Although anthropologists do not escape these mechanisms, they are attentive to the place they are given in a society, aware that it does not depend solely on them, and that finding this place takes time. They call to be vigilant to the reactions that their presence can arouse and to work only in or with companies when it is clearly accepted.

Many anthropologists would therefore probably take up the first part of Aruna HarPrasad's question:

"Who are we, to arrogate to us the right to disturb these people? "

And many, probably, regret that others - tourists in particular - arrogate to themselves the right to do so without authorization.

Listen

On the other hand, this question - and this is probably the essential difference between the posture of the anthropologist and that often defended in the media around the cases mentioned above - does not arise with regard to a supposedly "intact" nature. concerned, or even their "harmonious" relationship with nature.

Flora and fauna of North Andaman. Wiki Media, CC by

Listening to the expectations of the social groups that we work with or visit is seen as an ethical principle - defended by institutions, researchers and / or communities - whether these are "isolated" or no.

The question of the "acceptance" of the researcher in the society studied arises, for example, today in "indigenous" societies immersed in the technological and economic globalization, which call for a renewal of research practices so that these are more "collaborative" and less "colonial".

What a "society" as a whole thinks and wishes

One of the difficulties, of course, is knowing what a "society" as a whole thinks and wants - all societies have opposing lines of opposition and differing views about what is "acceptable" or not, including in tourism development.

Another difficulty comes from the reality of the power relations that can make the expression of a refusal of the tourist attendance complicated.

It is perhaps in this respect that the situation of the Sentinels and Jarawa, like that of other Aboriginal societies , is specific.

These societies have had a long history of discrimination and marginalization that can make them vulnerable and unable to make their voices heard when foreigners arrive, while in other cases they can take advantage of tourism as a political weapon in the recognition of their autochthony .

So we can not say once and for all that tourism development is positive or negative. It depends largely on the local situations and the power relations that are played out there - and in particular on the capacity of local actors to control tourist flows - but not, according to anthropologists, a supposed "isolated" or "primitive" nature. Of the companies visited.