New Ancient Ape Species Rewrites the Story of Bipedalism and Humans

/New Ancient Ape Species Rewrites the Story of Bipedalism

When Madelaine Böhme, a researcher at the University of Tübingen in Germany, unearthed the partial skeleton of an ancient ape at the Hammerschmiede clay pit in Bavaria, she knew she was looking at something special. Compared to fragments, an intact partial skeleton can tell paleoanthropologists about a creature’s body proportions and how its anatomy might have functioned. A relative newcomer to the field and a paleoclimatologist by trade, Böhme enlisted Begun’s expertise in analyzing the fossil ape.

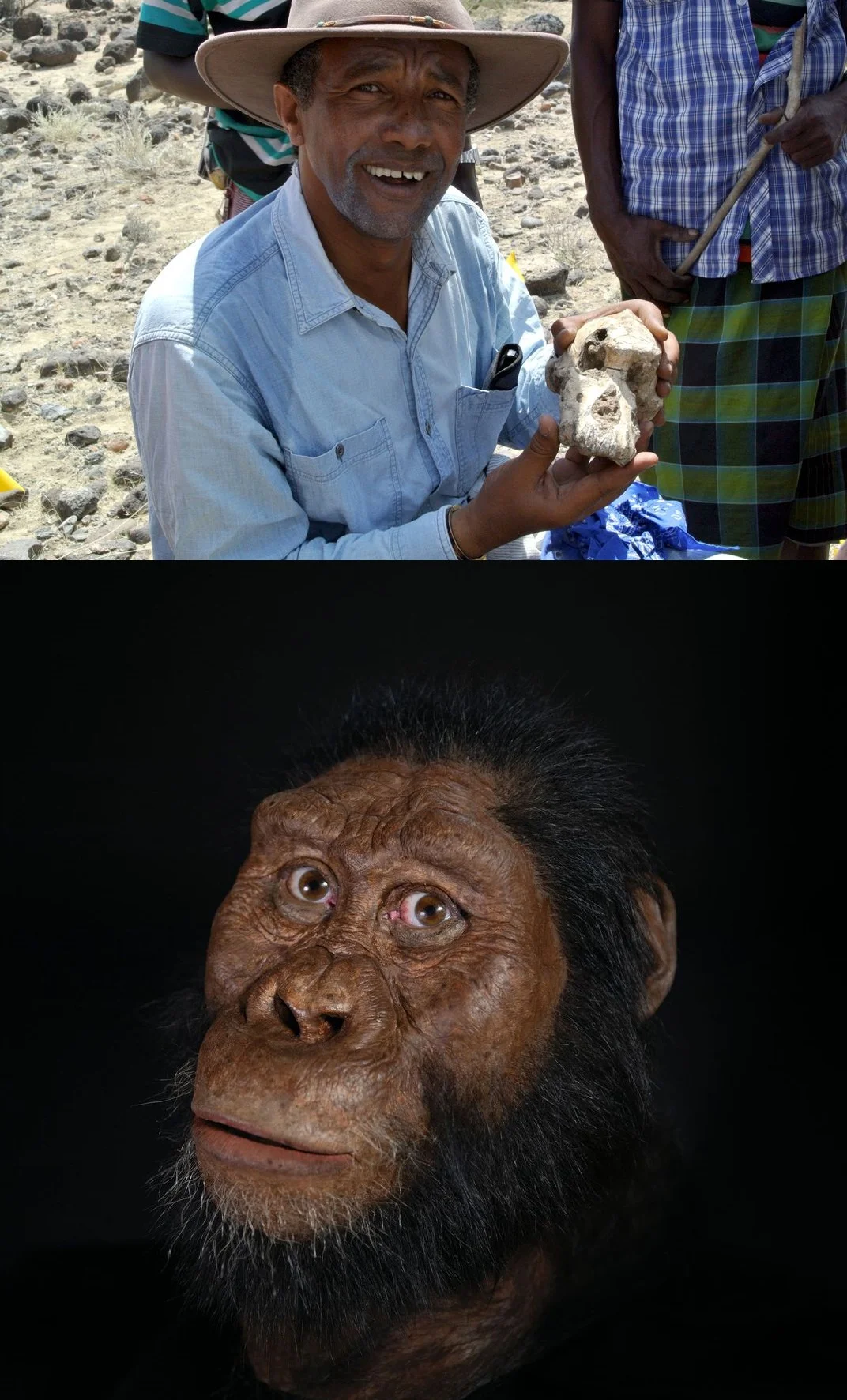

Böhme and colleagues determined that the bones they found came from a dryopithecine ape, an extinct ancestor of humans and great apes that once lived in the Miocene epoch. The fossils are approximately 11.6 million years old and came from at least four individual apes, including one partial skeleton. The team described the newfound ancestor, named Danuvius guggenmosi, in a study published today in Nature.

‘D. guggenmosi’ was likely a small primate about the size of baboon, with long arms like a bonobo. The creature had flexible elbows and strong hands capable of grasping, which suggests that it could have swung from tree to tree like a modern great ape. But the similarities with known apes stop there. The animal’s lower limbs have much more in common with human anatomy. With extended hips and knees, D. guggenmosi was capable of standing with a straighter posture than that of living African apes, and its knees and ankles were adapted to bear weight. The animal’s locomotion would have therefore shared similarities with both human and ape movement, and D. guggenmosi may have been able to navigate the forest by swinging from tree limbs and walking on two legs.